By Agnieszka Gautier

The Arctic is changing, shifting animal and plant life cycles to adapt to thinning ice and shorter winter seasons. To understand how small, regional processes are behaving, scientists are turning to the Arctic’s long-time residents. “Scientists are increasingly aware that Indigenous people have a deep and broad understanding of our changing environment and landscape,” said Peter Pulsifer, lead for the Exchange for Local Observations and Knowledge of the Arctic (ELOKA) program at NSIDC.

Technology offers new avenues for recording observations that have for generations been passed down through the oral tradition. But where does all this documented knowledge go? How can it be maintained to guarantee its preservation for future generations? And who has access to it? To answer some of these questions, ELOKA with its partners has developed several digital atlases, due to launch during the summer months of 2013.

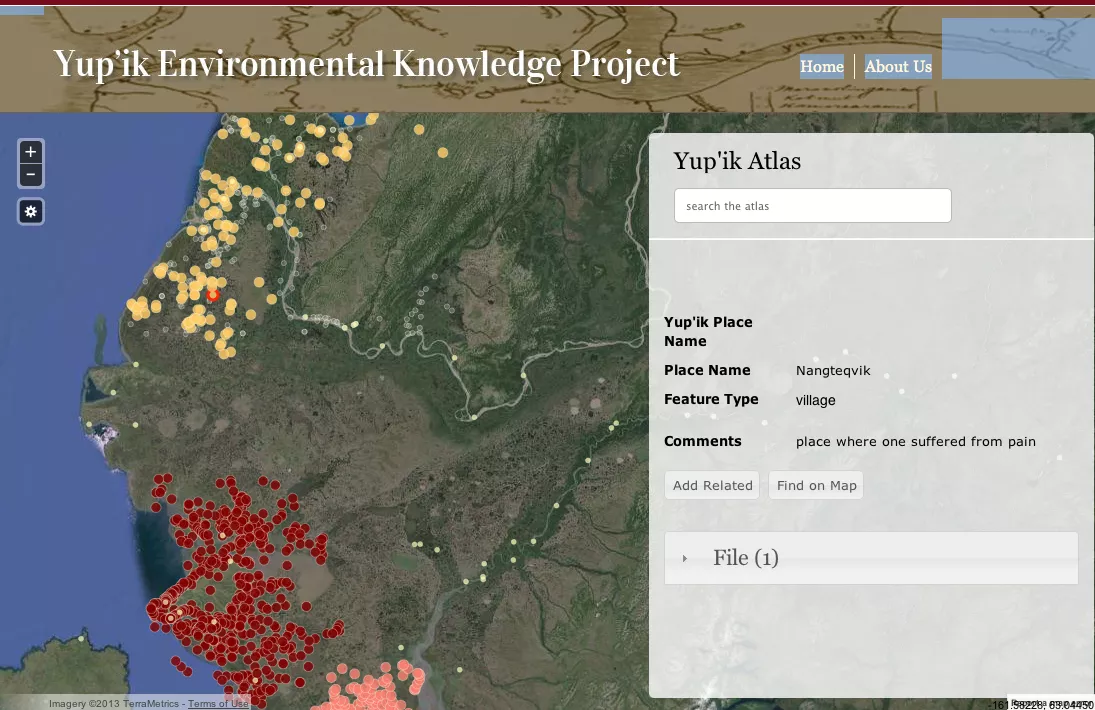

The Yup’ik Environmental Knowledge Project

Yup’ik elders recognize the power of names. “One who speared another” and “Place where one takes something out” are not just places, but gateways to stories. And within each one Yup’ik values unravel. That is why in partnership with the Calista Elders Council (CEC), ELOKA has developed the Yup’ik Environmental Knowledge Project website and online atlas. As a major research organization, the CEC has worked for ten years with elders from Bering Sea coastal communities to document Yup’ik place names.

Elder John Phillip of Kongiganak says, “Today people travel at fast speeds using snow machines. Many fail to recognize places they pass and lose their way. Elders instruct that continual observation is still important and can be a matter of life and death.” With insight into Yup’ik culture, values, and languages, the website provides Yup’ik and English translation text, photos, audio, and video files to be associated with more than 3,000 identified place names in the online atlas.

The Atlas of Community-Based Monitoring in a Changing Arctic

Changes that are not good for the reindeer are not good for the Nenet people. With dramatic shifts in their landscape, these nomadic reindeer herders struggle to maintain a thousand-year-old tradition on the Yamal Peninsula in Northwest Siberia. Staying too long in one place can be a matter of life or death. Rivers are surging in early winter, instead of freezing and providing safe passage. Ancient permafrost thaws and drains away lakes. Gnat fly populations increase while mosquitoes decrease. Longer autumns lead to delayed springs. The Nenet people continue monitoring such changes, as well as their own social shifts.

They are not alone. Many Arctic Indigenous communities are learning to apply observation and monitoring practices in new and collaborative ways. The Atlas of Community-Based Monitoring in a Changing Arctic (http://www.arcticcbm.org) is mapping both traditional knowledge and scientific approaches to monitor community concerns, including sea ice, snow cover, weather, biodiversity, and water quality. The Atlas serves as an important resource for local and sometimes regional or national decision-making. The project is a partnership between Inuit Circumpolar Council Canada (lead), Brown University, Inuit Quajisarvingat: The Inuit Knowledge Center, and ELOKA.

The PHENARC Project

With prolonged autumns and delayed winters, migratory birds arrive at the “wrong” times. The first bloom is a significant marker for researchers studying the shifts in plant and animal cycles, but for the communities that live through these changes, it is a matter of survival. Susan Crate at George Mason University (GMU) involves communities in northeastern Siberia and in the Labrador/Nunatsiavut areas in studying links between Arctic phenology and climate change.

In northeastern Siberia, changes in snow cover affect the Viliui Sakha, who depend on their horse and cattle breeding practices. Here snow remains on the ground about a month longer than usual, delaying spring, shortening the growing season, ruining the berry season, and sometimes starving horse and cattle populations on thinning pastures. A thousand years ago, Viking would-be settlers named the Labrador/Nunatsiavut region “Markland,” or forest-land, a sub-arctic forest too brutal from some. Still the determined integrated, developing a culture of diverse traditions. Today, 30 percent of Labradoreans are Aboriginal people, once drawn here by the abundance of whales. Shifts in sea ice cover impact all these communities and their relationship to the area’s rich fishing industry.

For both regions, the PHENARC atlases will allow community members to delineate routes and record points of interest with the ability to attach observations, stories, pictures/videos, and other materials to each path and point. The first atlas to be developed will involve the community of Makkovik in Nunatsiavut, where school children, Elders, and a local museum will take part in populating the atlas. “Helping to develop tools like the atlases enables broad sharing of knowledge, now and in the future,” said Pulsifer. “Such information will help all of us deal with the local, regional and global effects of a rapidly changing Arctic.”

More information

ELOKA Yup'ik Environmental Knowledge Project The Atlas of Community-Based Monitoring in a Changing Arctic The PHENARC Project