By Agnieszka Gautier

What’s the use of data that is difficult to retrieve? The Semantic Sea Ice Interoperability Initiative (SSIII), a project at NSIDC, tries to tackle the challenge of organizing data within language systems. “Semantics is a big thing in web technologies and it’s how you can get computers to understand the concepts beneath words,” said Ruth Duerr, NSIDC’s informatics team lead. “It puts the smarts in your ability to build tools for users,” she said. A smart enough tool knows to search for various forms of precipitation when asked to find rainfall data. It has made the link between rainfall and precipitation. This is basic semantics.

On naming

SSIII wants to bring semantic technology to the Arctic data community. Using nomenclature from the World Meteorological Organization, the team garnered a set of sea-ice terms. “It’s turned out to be very interesting,” said Duerr. “People may not necessarily realize that the terms they’re using are not as logically organized as they thought. We kept running into small issues.”

Finding data gets complicated when disparate groups use their own terminologies. “They may use the same word for different things or use different words for the same things,” Duerr said.

Let’s deconstruct sea ice. Is it simply defined as frozen seawater? Not for the floating chunks of freshwater ice calved from the Greenland ice sheet. They may float in the sea, but they are freshwater. And when is there no sea ice Remote sensing scientists say that it is when less than 15 percent of the surface is covered in ice, because remote sensing microwave satellites can no longer see it. That, however, is not a definition that works well with mariners because that 15 percent may still cause serious damage to boats and ships.

After collecting the essential nomenclature, the team needed to turn it into series of ontologies. The term ontology has its roots in a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of reality or metaphysics. For informational science, ontology refers to an explicit (machine-readable) and formal representation of concepts and their relationship. Ontologies attempt to circumvent the ambiguity and vagueness of natural language. Structures must, therefore, be well defined. Though quite abstract, the basic premise is to group concepts within a domain to establish fixed, controlled vocabularies of rich and complex knowledge about things, groups of things and the relations between things. It attempts to make implicit knowledge explicit.

On the backs of napkins

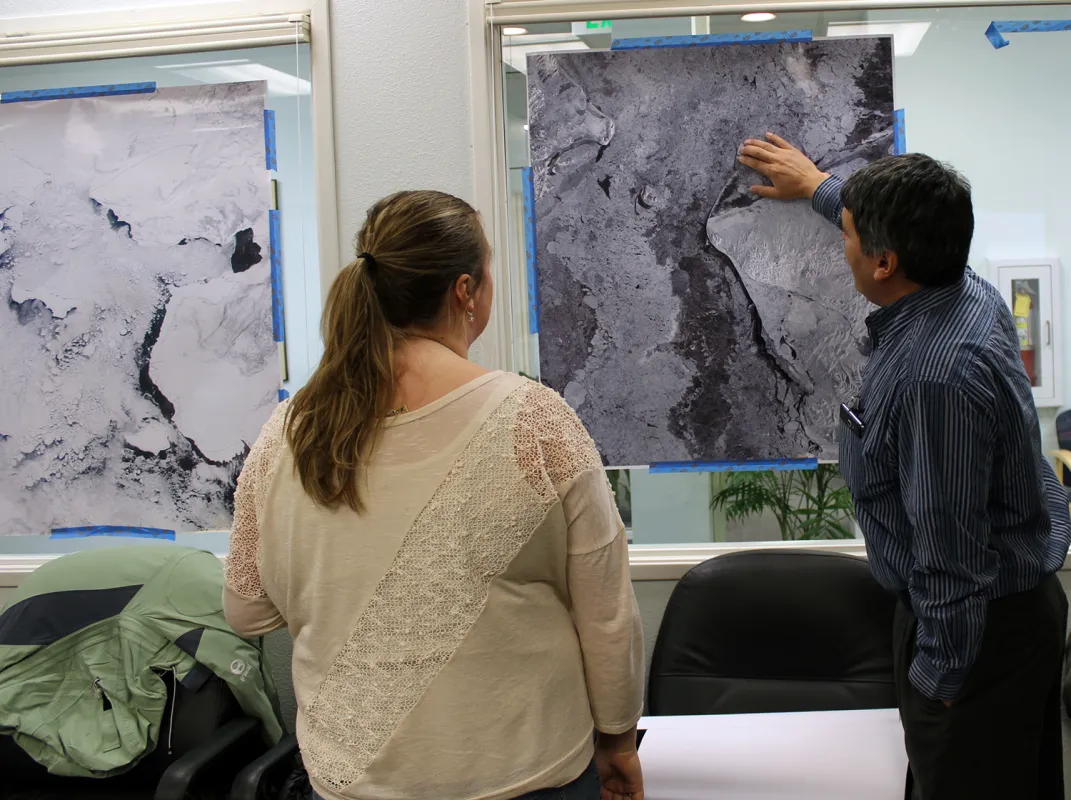

Creating a set of ontologies in the same language is challenging enough, but what about working with multiple languages? “It’s one thing to say we want doctors from different hospitals sharing information,” said Peter Pulsifer, a lead for the Exchange for Local Observations and Knowledge of the Arctic (ELOKA), “but it’s another thing to say we want doctors to share information with theologians, for example.” ELOKA deals with Indigenous knowledge of sea ice. How does a historically oral tradition translate to written language, let alone an information system environment? “We don’t know if this is an appropriate method with Indigenous knowledge and terminology,” said Pulsifer. “So what we’re trying to do here is learn.”

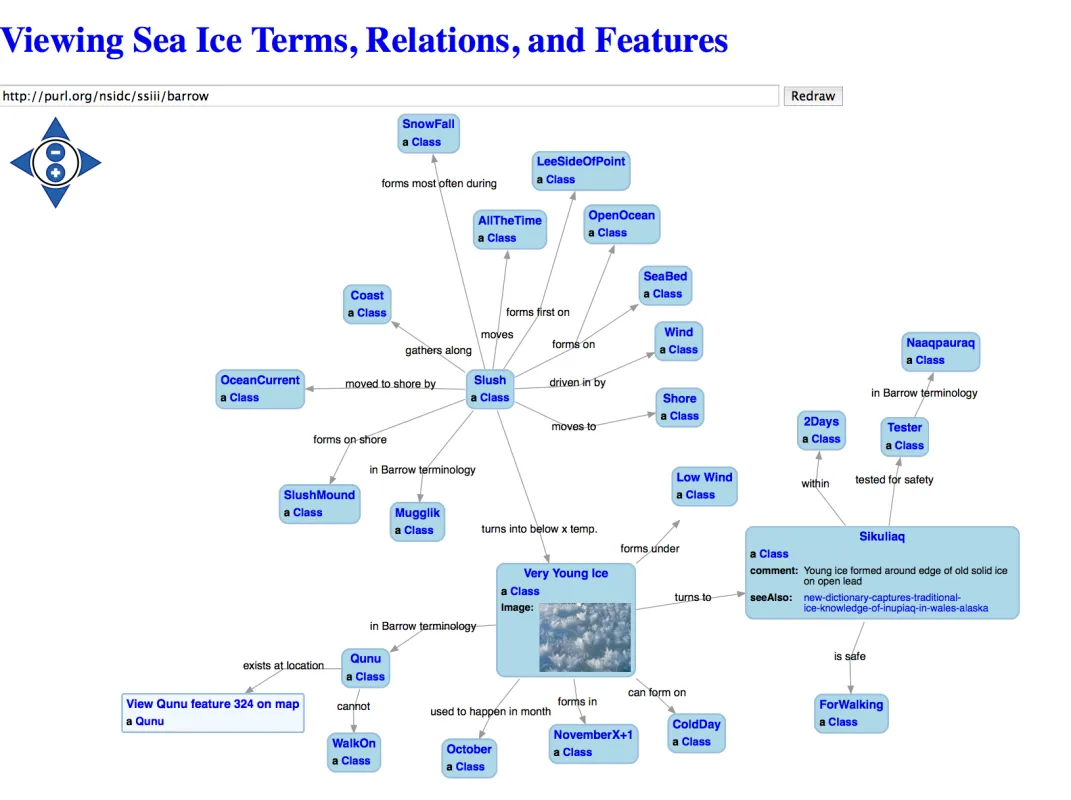

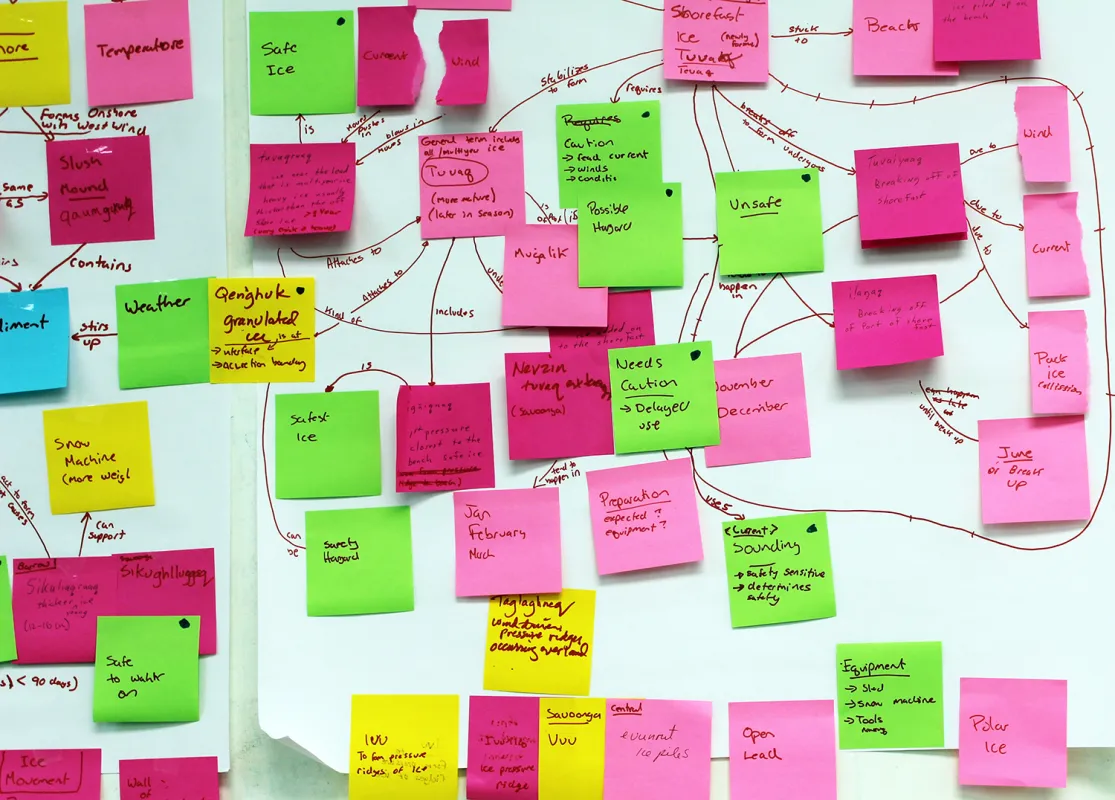

To make the appropriate links between scientific and operational vernacular, Pulsifer is using methods such as concept mapping or diagramming to visually organize Indigenous terms and concepts. “Concept maps are great for human beings,” said Pulsifer. “They provide a fast recognition of patterns. But computer based systems can’t handle the graphic component.” Concept maps need to be transformed into statements or assertions with a reasoning end, meaning implementing logic to establish links and relationships between ideas. For instance, if an assertion is made that a particular sea ice phenomenon melts at -3 degrees Celsius, it can then be inferred that if the temperature is recorded at -1 degree Celsius, sea ice in this area is likely melting.

Practical applications

Concept maps can get tricky as they cross many disciplines. And trying to share data across communities that already aren’t working together complicates semantics, to say the least. “We’re not at a place where we can say SSIII and semantic approaches are a panacea, where all the issues can be resolved,” said Pulsifer. “As you get deeper into multidisciplinary questions and environments, it becomes even more challenging.”

An outcome to SSIII’s research has been the development of hands-on teaching tools. Using Barrow, Alaska as a case study on sea ice safety, two products—a poster and website—resulted, showcasing how well various domains can be linked. Designed as a flow chart, the poster offers scientists and graduate students, who have little to no experience with sea ice safety, a visual aid in making decisions regarding sea ice concerns.

The website is a visual representation of a concept map that includes photographs, audio, and will eventually include video of sea ice and weather phenomenon. Pulisfer added, “We’re looking at this research from a holistic perspective. It’s not simply a technical act with a best route or effective method for any particular community but one that needs a larger perspective as well.”

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number 0956010. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.