A Nenets herder cut open the abdomen of a thawed reindeer carcass to find its guts empty. “There was [also] no fat around the heart,” said the herder Alex Serotetto. This confirmed the animal had starved—as had tens of thousands of reindeer on the Yamal Peninsula in northeastern Siberia in 2013.

Alex’s sobering observation is just one captivating part of the StoryMap “When Rains Fell in Winter,” which was nominated for Esri’s 2023 StoryMap competition and ended up on the company’s top ten favorite list, beating out hundreds published that year. Esri owns the geographic information system (GIS) software known as ArcGIS that supports StoryMapping.

A StoryMap is an online application that creates an interactive narrative, combining storytelling with locations through multimedia content. “StoryMaps can be like scientific community’s version of a long-form journalism platform,” said Irina Wang, one of the authors of “When Rains Fell in Winter.”

Irina worked on the piece with Philip Burgess, a project planner at the Arctic Centre at the University of Lapland in Rovaniemi, Finland. The Center aims to tell the story of the far north utilizing Arctic research and scientific communication, rendering them a perfect outreach partner for the Arctic Rain on Snow Study (AROSS) project, led by the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). AROSS researchers and others provided photographs and video footage of the Nenets to include in the StoryMap.

In addition to being published online, the “When Rains Fell in Winter” StoryMap will be featured in an extreme Arctic weather exhibit at the Center’s Arktikum Science Centre. The interactive nature of the StoryMap medium can leave lasting impressions on viewers. “Telling a more personal and singular story can be more engaging for general audiences to learn about the scientific processes behind Arctic change that may be otherwise inaccessible or a bit too abstract,” Irina said.

The end of the land

“When Rains Fell in Winter” follows the Nenets reindeer herder Tokcha Khudi and his family through the migration season on that fateful winter in 2013. That year, a series of rainstorms crusted snow with an impenetrable layer of ice. “The ice was like an iron cover; it was as hard as the surface of this table,” said Khauly Laptander, a herder also quoted in the StoryMap.

Unable to crack the ice and reach vegetation beneath, more than 60,000 reindeer starved. A combination of knowledge, skills, and luck saved the Tokcha-led herd from complete decimation, while many other herds were not so lucky.

For his entire life, Tokcha has herded reindeer across the Yamal tundra, an Arctic low-land peninsula in Siberia, as did his ancestors for thousands of years before him. Yamal translates to “end of the world” from Nenets. “It’s an absolutely magical place,” said Philip, who had visited with Nenets herders in the winter of 2014. “Just seeing the scale and immense landscape was amazing—its lack of roads, coupled with witnessing first-hand the Nenets’ close relationship with the animals.”

The permafrost-rich peninsula is 700 kilometers (435 miles) long with a maximum width of 240 kilometers (150 miles). Around 6,000 Nenets herders guide 275,000 reindeer to forage across the Yamal annually. It is, therefore, common to cross paths with other herds, but each herder knows their own animals, keeping to their claimed migratory routes.

Though the families are ultimately harvesting reindeer for their meat, for profit and subsistence, every decision and movement promotes optimal health for the animals. “There is no sentimental attachment to the animals, but everything they do is for their safety and good,” Philip said. “They have this deep knowledge of how the herd works and it is extraordinary to see.”

In search of pastures and mushrooms (a reindeer favorite in late summer), the migration heads north as the days lengthen in the summer, navigating a land littered with swamp and bogs. Pockets of camps pop up around the region’s thousands of lakes, where fishing becomes a major source of food for the families. Then, as the days shorten, the herders head south seeking the last remnants of a summer’s feast. Every year, this migration yields about 1,200 kilometers (746 miles)—a distance equivalent to a round trip journey from Denver, Colorado, to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

“The herders are in these ecological niches on the peninsula as they move north and south according to climate. Each area is a perfect place for a perfect time,” Philip said. “And that’s why these shifting climate patterns are so risky, because if you get one event like that in 2013, one problem in one area cascades through the whole system. It turns the entire enterprise upside down.” The StoryMap tackles how that system breaks down as a family makes choices and decisions to adapt to the resulting environmental consequences.

Making a StoryMap: Putting the pieces together

The “When Rain Falls in Winter” StoryMap burgeoned into a highly collaborative project that spanned several countries and organizations, bringing together people from different areas of expertise. While Philip focused on the narrative for the StoryMap, Irina matched the content with imagery and design.

When the AROSS project began in 2019, many researchers and communicators had hoped to travel to Yamal to gain firsthand perspective on more recent rain-on-snow events, not just the catastrophic 2013 event. But the global pandemic and then Russia’s invasion into Ukraine in February 2022 thwarted those efforts. So, Irina and Philip turned to Florian Stammler, an Arctic researcher, and Roza Laptander, a Nenets sociolinguist and AROSS team member, who provided earlier recordings, photos, and videos of the Nenets gained from their own research in the region.

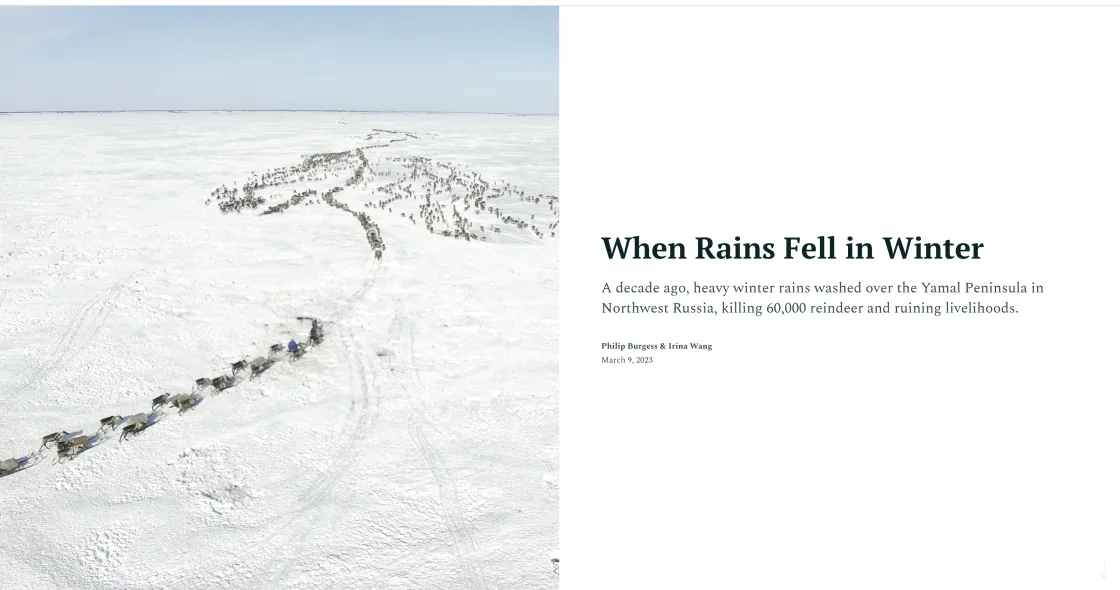

“When Rains Fell in Winter” interweaves text and image, taking viewers on an immersive and emotional journey through the 2013 rain-on-snow event. It opens with a bright white page with a photo of snow-blanketed tundra and strings of reindeer wandering into the horizon. As you scroll down the page, text is sparse, punctuated by complimentary video and photos. “I didn’t edit a lot of the images,” Irina said, “especially those lovely ones from 2001 that Florian took. They have such a wonderful vintage quality.” The yellowed images could have been taken a hundred years ago, capturing the faces of a reindeer-herding family: a father and son pulling a sled over, Tokcha among his herd, an elderly woman sewing, and a huddled group of children.

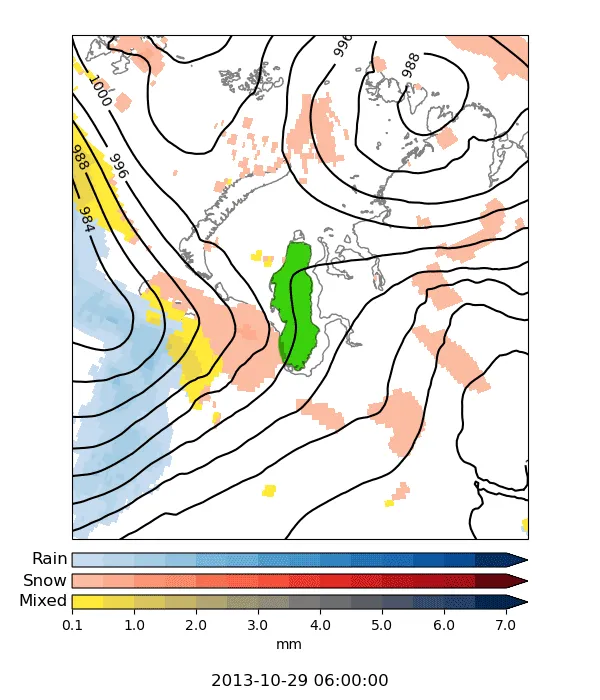

As scrolling continues, maps navigate the reader across the landscape through various points in the migration, orienting the reader to its cyclical nature, until the section entitled “Rain at the Wrong Time” brings into focus an AROSS created meteorological animation.

The disruption is visual as well as practical. The sudden rain-on-snow event affected the pastures to the south of the migration, where most herders were heading. Scattered icing covered an area the size of Belgium or the state of Pennsylvania. “When it happened, chaos ensued,” states the StoryMap under the section “Serad Po—A Year of Misery.” The timing of the event made things worse. While other months offer flexibility, November offers no “wiggle room” when timing is tight as herders have a small window to head back south for the winter.

Further down the StoryMap, a screen-wide photo appears of frozen and emaciated reindeer carcasses. The narrative centers on Tokcha, who with skill and luck, made the right call. Instead of heading south as is typical for this time, he retracted back north. A dark map, contrasting earlier maps, shows Tokcha’s retraced route in bright red, emphasizing the importance of his decision.

The piece continues with voices and quotes from other herders who lost nearly entire herds. And then it ends with a photo of Tokcha’s now-grown son Andrei taking the reins from his father with a bit more modernity; Andrei utilizes a trailer and snowmobile instead of the traditional castrated male reindeer pulling the camps and supplies.

A communication tool worth the effort

According to Irina, StoryMaps are easy to use and intuitive to put together. Each section is a block that can be modified within the scrolling structure. “The StoryMap is made to be more immersive,” said Philip. “People don’t spend long on web stories and quickly click away. Whereas on StoryMaps, they can spend four to five minutes on them. It’s hard to capture people’s attention nowadays. If you have a good story and good images and you can tell it well, then people will read it.”

Irina and Philip had not expected the StoryMap to receive so much recognition. Part of its success is that the StoryMap tool is captivating. “It’s always challenging for academics to tell their stories in an engaging way,” Philip said. “Strong science communication is generally not a skill academics have.” Working on the StoryMap brought home to Philip, a seasoned science communicator, just how timely proper science communication is. “It’s something that can’t be underestimated or skimped on in the budget,” Philip added. “It’s so important to create innovative communication built on really hard science. People who can tell a story in an engaging way will get more people to care about the issue.”

In the wake of “When Winds Fall in Winter,” Irina and Philip are working on a follow-up StoryMap that confronts the issues facing Finnish and Sámi reindeer herders, who are beginning to rely more heavily on supplemental feeding. Unlike the Nenets, many reindeer herders in Scandinavia and Finland shifted away from a nomadic lifestyle in the 1960s and 1970s as deforestation and land development fragmented migratory routes. “Nenets might say that is not reindeer herding anymore,” Philip said, “but that is harsh when southern Finland no longer has any good winter pastures left.” Many reindeer are enclosed and fed in winter. Factories have expanded their product lines to make costly feed, trucks sometimes transport the animals, and herding routes have been fenced. Herding has become highly constricted as the demands of the industrial and postindustrial world creep in.

The Nenets have their own challenges, but Philip said, the Nenets don’t think of themselves as victims. The herders say, “We’ve managed before, we’ll adapt.”

After all, the Nenets lived through the Soviet Union and the collectivization of their privately-owned animals. “They’re still here and the Soviet Union is gone,” Philip said. “They’re still migrating in the same paths they used to, but the climate science is not looking good.” Yamal is a low-lying landmass and sea-level rise could have huge impacts. As rain-on-snow events become more prevalent, the Nenets hope to work with scientists to gain insight into potential catastrophes before they occur. Science may help them prepare, but the question remains, for how long? “Skill and luck saved most of Tokcha’s herd,” Philip said. “But the fear is that knowledge and skill will not be enough in the future.”

For more information

Inventory of Arctic Rain on Snow Events: Meteorological and Surface Conditions, Version 1