April 2023 snow summary

Snow-covered area for the western United States was 231 percent of average for April, the highest for the second month in a row since the satellite record began in 2001.

Snow cover days surpassed the previous satellite-record maximum in early April.

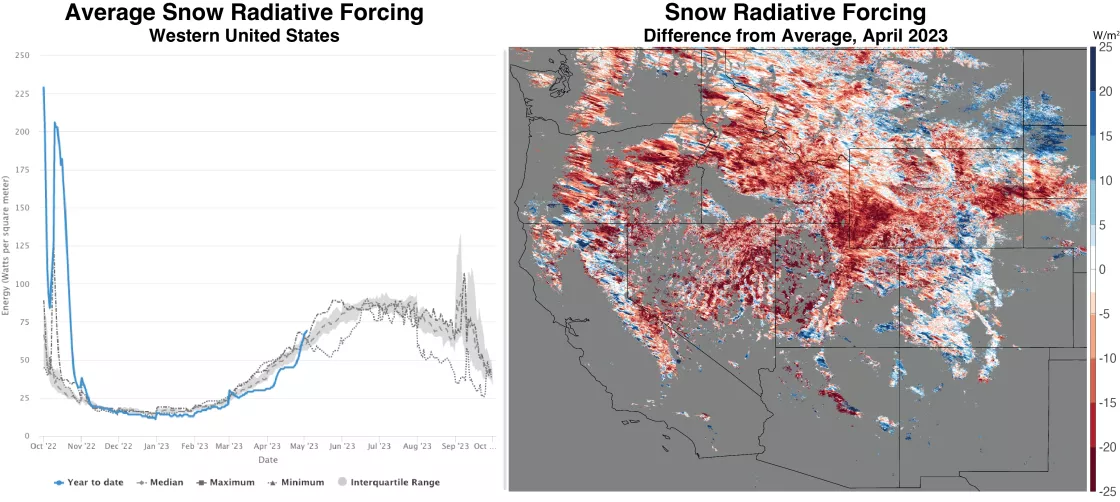

High snow albedo and low snow radiative forcing persisted for most of April, but the snowpack brightness quickly moved to average values near the end of the month.

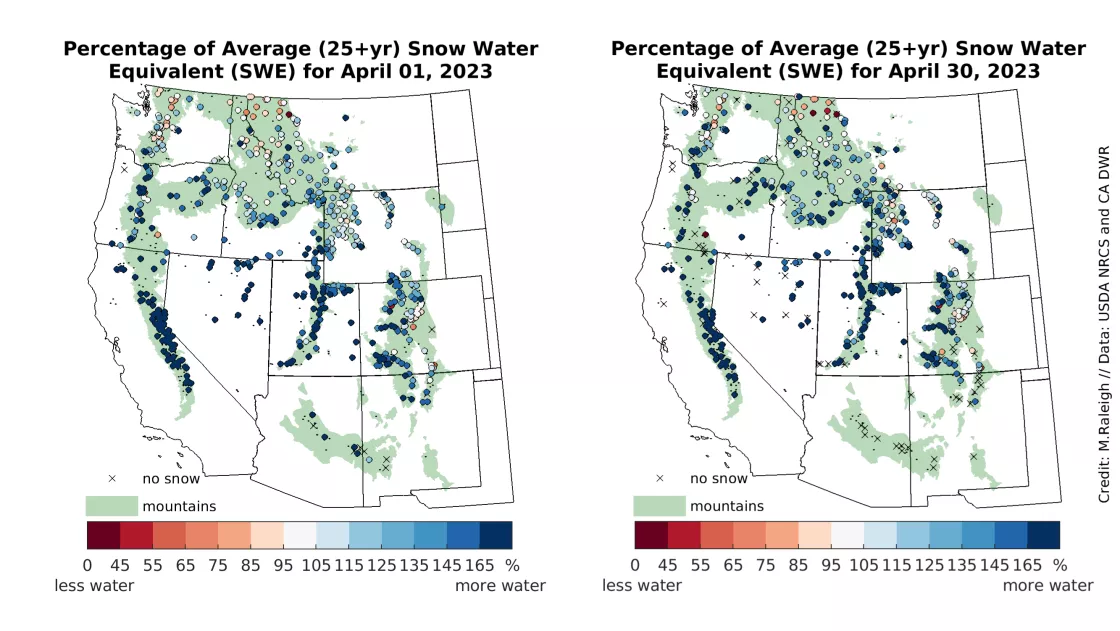

Snow water equivalent (SWE) was above average in all western states in April, with California, Nevada, and Utah continuing to register the highest values relative to average.

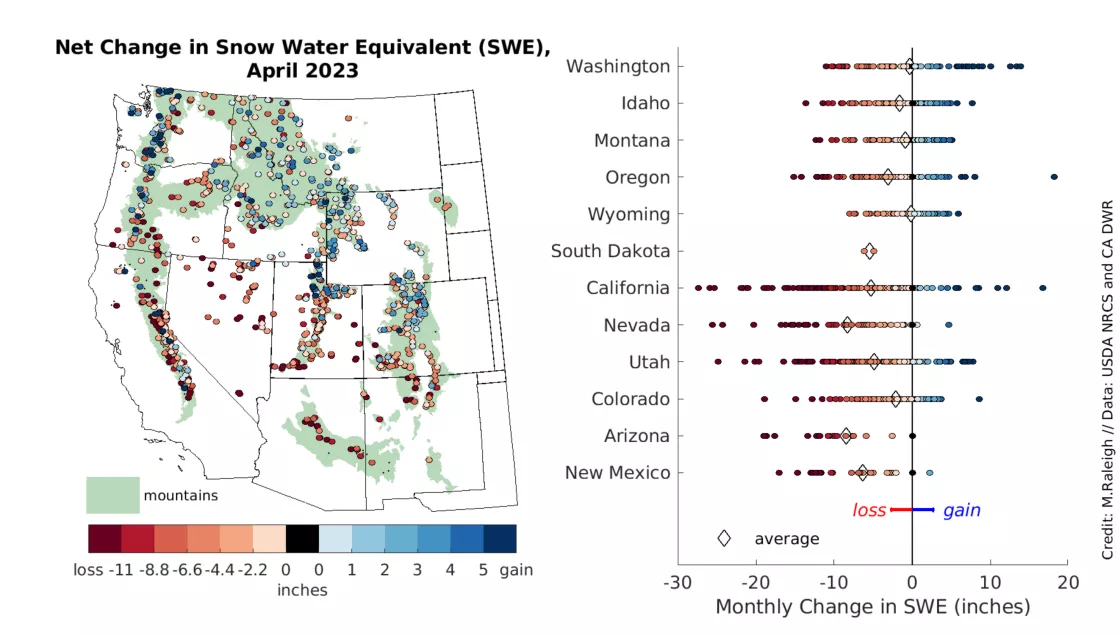

Snowmelt was underway at many SWE stations, with 64 percent having net SWE losses through April.

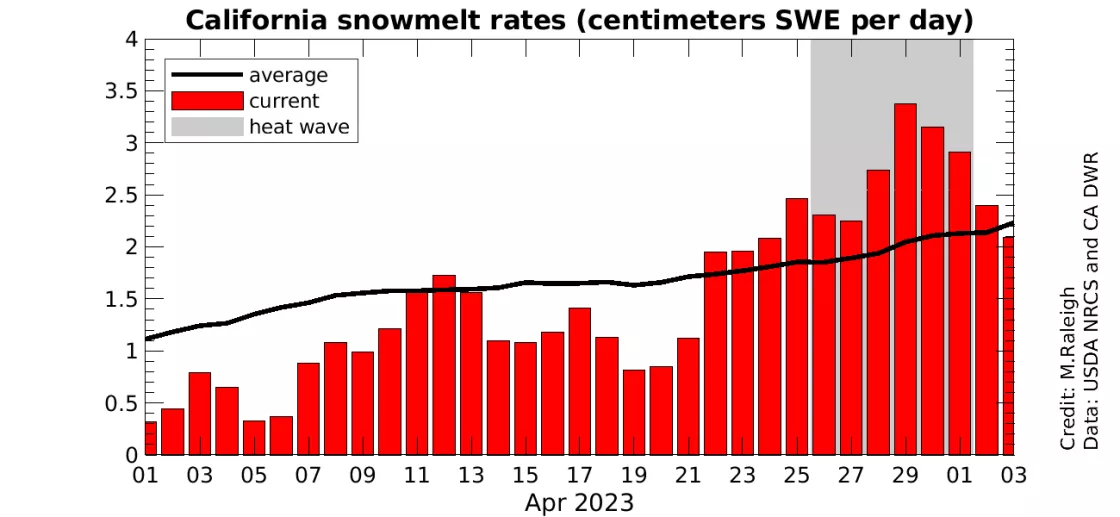

The large snowpack in California had substantial melt during a heat wave event late in April.

Overview of conditions

Table 1. April 2023 Snow Cover in the Western United States, Relative to the 23-year Satellite Record

Snow-Covered Area | Square Kilometers | Square Miles | Rank |

April 2023 | 827,000 | 319,000 | 1 |

2001 to 2022, Average | 357,000 | 138,000 | -- |

2008, Second Highest | 500,000 | 193,000 | 2 |

2015, Lowest | 193,000 | 75,000 | 23 |

2022, Last Year | 368,000 | 142,000 | 11 |

Snow-covered area for the western United States hit another record for April, the second month in a row since the satellite record began in 2001. Snow-covered area was 231 percent of average. For perspective, compared to an average February, when snow cover tends to be the most extensive, snow cover in April 2023 was 91 percent of an average February. The snow-covered area for April 2023 was 165 percent of the second highest year, 2008 and more than four times the area in 2015, the lowest year. April 2023 had over twice the amount of area than last year.

Snow-covered area in April 2023 was above average in all states and large river basins except for the Arkansas-White-Red which had 98 percent of average snow-covered area. This pattern in April was similar to the prevailing condition from March 2023. However, some states had significant declines of nearly 100 percent of average relative to March snow-covered area. The states with the largest snow loss were Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, and South Dakota, as well as the Missouri River basin. By contrast, both the Upper and Lower Colorado River basins had higher percentages of average relative to March while the Great Basin remained unchanged. Arizona and Nevada stood out as the states with the highest percentages of average. In Arizona, snow lingered in only two locations: the Kaibab National Forest, home to the Grand Canyon, and the White Mountains near Flagstaff.

Conditions in context: snow cover

While snow-covered area across the western United States topped the record, in the absence of spring storms and more sunlight, it decreased rapidly through April (Figure 2, upper left). At this time of year, lower elevations lose snow cover rapidly while higher elevations with deeper snowpacks maintain coverage later into the year. Across the western United States, the highest elevations have near average snow-covered area. Moderate to low elevations along the edges of mountain ranges have 20 to 100 percent more snow cover over the month of April relative to the 23-year average (Figure 2, upper right). While this pattern is widespread, the extensive areas with above average snow cover were north of the Uinta Mountains in Utah and in northeast Oregon in the Aldrich mountains and Columbia Plateau.

Snow cover days averaged over the western United States, from October 1 to April 30 continued to increase, surpassing all other years in the 23-year satellite record (Figure 2, lower left). Significant areas had 40 to 100 more snow cover days than an average winter (Figure 2, lower right). Portions of southeastern Oregon, California's Sierra Nevada and White Mountains, and the ranges and many basins of Nevada had the highest number of snow cover days relative to the average. A few areas in Colorado and New Mexico like the Sangre de Cristo Range, Wet Mountains, and Mosquito range west of Colorado Springs, had below average snow cover days. Snow cover days in northern Washington and northwest of Helena Montana were also below average. A few other isolated locations had below average snow cover days.

Snow brightness, known as snow albedo, is impacted by the age of snow (size of surface snow grains) and impurities such as dust, industrial emissions, wildfires, and leaf litter. These impurities increase the snow radiative forcing by absorbing more solar energy, which melts out the snowpack faster. This winter, accumulation of these light-absorbing particles on the snow surface was below average for most of the season including the month of April (Figure 3, left). However, rapid melt exposed many of the particles on the darker snow surface increasing radiative forcing by the end of the month. Despite this change, when averaged over April, most regions had lower radiative forcing than average (Figure 3, right).

Conditions in context: snow water equivalent (SWE)

Regional patterns in snow water equivalent (SWE) were similar at the beginning and end of April 2023, based on measurements at the SWE stations (Figure 4). Relative to the long-term records, SWE was above average at 88 percent of stations across the western United States at the start of April. On a statewide average basis, all states had above average SWE over the month. Locations with the greatest SWE values relative to average included California, Nevada, and Utah, which were over 200 percent of average. Notably, SWE percentage of average increased in Oregon from 139 to 174 percent through April. All other states had SWE percent of average ranging from 112 to 150 percent at the end of April. The lowest SWE percentages were found in more northern locations including Washington and Montana, which still had 112 and 117 percent of average, respectively. With warmer conditions, melt was underway at many locations, and snow melted out at most stations in Arizona and New Mexico, and several stations in Nevada (Figure 4, right “x” markers).

As noted above, the snowpack at many stations experienced snowmelt through April, and this is seen in the map of net SWE change (Figure 5). Over the full domain, 64 percent of stations reported a net loss in SWE, 29 percent of stations reported a net gain in SWE, while 7 percent of stations reported no net loss or gain in SWE. There was a regional pattern (Figure 5, left), with net SWE losses more prevalent in the southwestern part of the domain (e.g., California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona) and net SWE gains more common toward the northeast (e.g., northern Colorado, northern Utah, Wyoming, southern Montana). Averaged across all SWE stations in each state, all states had a net SWE loss (Figure 5, right, diamonds). Arizona had the greatest average SWE loss at 24.9 centimeters (9.8 inches), while Wyoming had the lowest average SWE loss at 0.5 centimeters (0.2 inches).

Individual stations showed larger net SWE changes than these statewide averages (Figure 5, right). The largest decrease in SWE was found at the Robb’s Powerhouse station in the American River basin of California, with 68.6 centimeters (27.0 inches) of net SWE loss, and complete melt out on April 28. Six other stations in California, Nevada, and Utah had substantial losses of SWE in excess of 61 centimeters (24 inches). By contrast, there were some stations reporting net SWE gains in all states, with the exceptions of Arizona and South Dakota (Figure 5). The largest gain in net SWE was at the Bear Grass station in the central Oregon Cascades, which had a SWE gain of 46.2 centimeters (18.2 inches). A handful of other stations in the Cascades had SWE gains exceeding 31.8 centimeters (12.5 inches).

Mega California snowpack begins heating up

A major story this winter has been the historically large snowpack in the California Sierra Nevada. Snow Today has been tracking the snow cover and SWE values of this snowpack and providing context, as reported in previous articles. With the arrival of spring and warmer weather, concerns arise for how quickly the snowpack may melt with potential for flood risks. April had widespread melt over much of the western United States, with substantial SWE losses in California (Figure 5). The progression of California snowmelt through April was uneven, however. The first week of April had snowmelt rates well below the long-term average for that time of year (Figure 6), and with snowmelt occurring at only 15 to 30 percent of stations. This was followed by another two weeks of generally modest melt rates, but snowmelt occurred at 50 to 90 percent of stations. It was not until the third week of the month that melt rates began accelerating, and the final nine days of the month all had above average melt rates (Figure 6), with snowmelt at 74 to 98 percent of stations. This rapid and widespread melt at the end of April was punctuated by an early-season heat wave, which brought the highest snowmelt rates for the month, including one day, April 29, when snowmelt rates reached nearly 65 percent above average. These analysis results were averaged on a statewide basis, and higher melt rates were observed at more localized areas. With longer days, more sun, and increasing temperatures in the coming months, higher melt rates are likely to be on the horizon.