After a period of rapid sea ice loss extending into the last week of August, the rate has slowed with the onset of autumn in the Arctic. A region of low concentration ice persists in the Beaufort Sea. How much of this ice melts over in the next two weeks will strongly determine where the September sea ice minimum will stand in the record books. The Northwest Passage (Amundsen’s route) is largely open but some ice remains. The Northern Sea Route, along the Siberian coast, remains open.

Overview of conditions

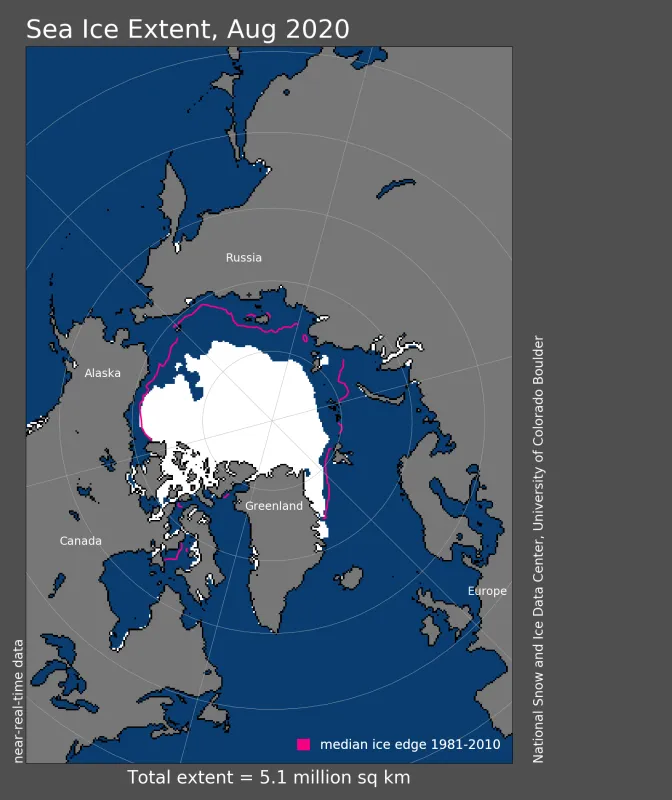

August 2020 sea ice extent averaged 5.08 million square kilometers (1.96 million square miles), placing it at third lowest in the satellite record for the month. This was 360,000 square kilometers (139,000 square miles) above the record low set in 2012. As of September 1, Arctic sea ice extent stood at 4.26 million square kilometers (1.64 million square miles), the second lowest extent for that date in the satellite passive microwave record that started in 1979.

In our previous post, we noted the development of substantial openings of the sea ice north of Alaska within the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas, possibly related to the mid-July storm that spread out the ice cover. Since then, further melt has occurred in the area. Some of this ice appears to be multiyear, which tends to be resistant to melting away. Total sea ice extent at the September minimum will depend strongly on how much of the ice in this area melts from the remaining heat in the ocean, and on wind compaction or expansion of the overall ice edge (the line of 15 percent concentration). The Northwest Passage is largely open, but some ice remains. The Northern Sea route remains open.

Conditions in context

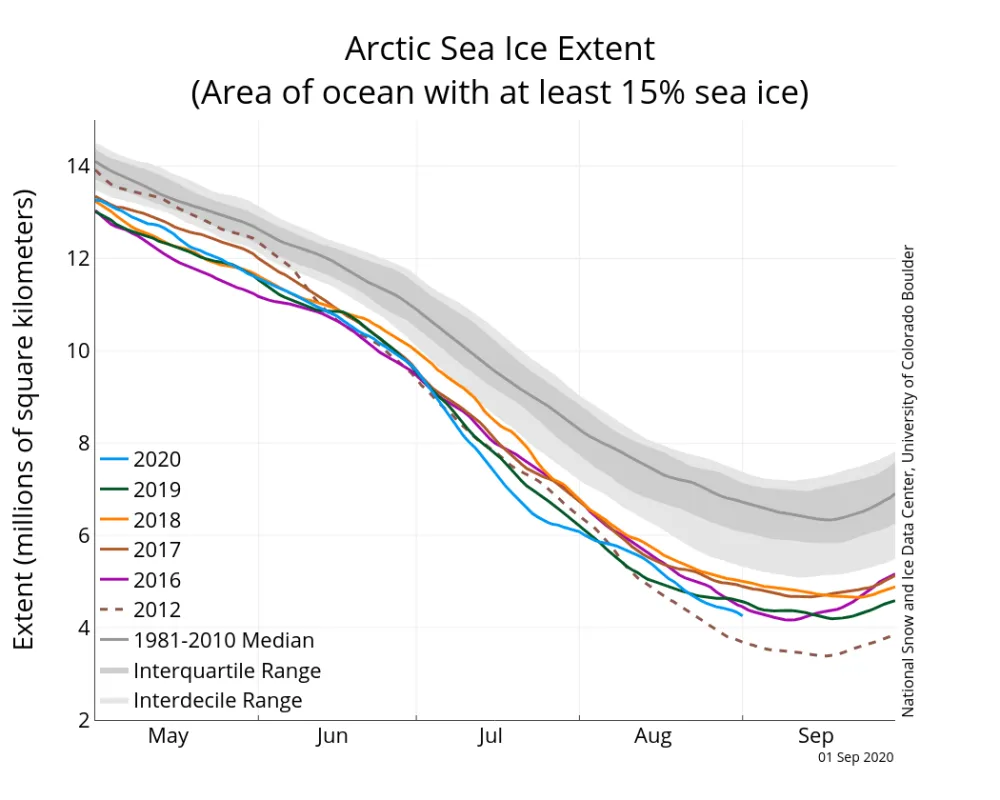

Following a period of slow August ice loss, the pace quickened during the middle of the month as areas of low ice concentration melted away, only to slow again towards the end of the month with the onset of autumn in the Arctic. Overall, from August 15 through September 1, 2020, extent declined by 1.1 million square kilometers (425,000 square miles), more than the average 1981 to 2020 extent loss of 800,000 square kilometers (309,000 square miles) during the same period (Figure 2a).

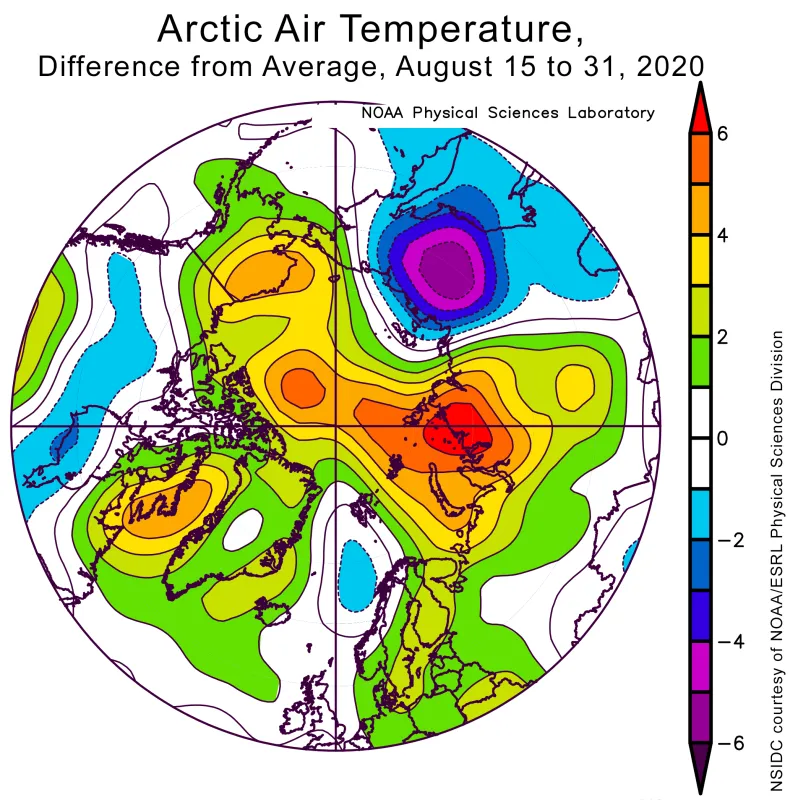

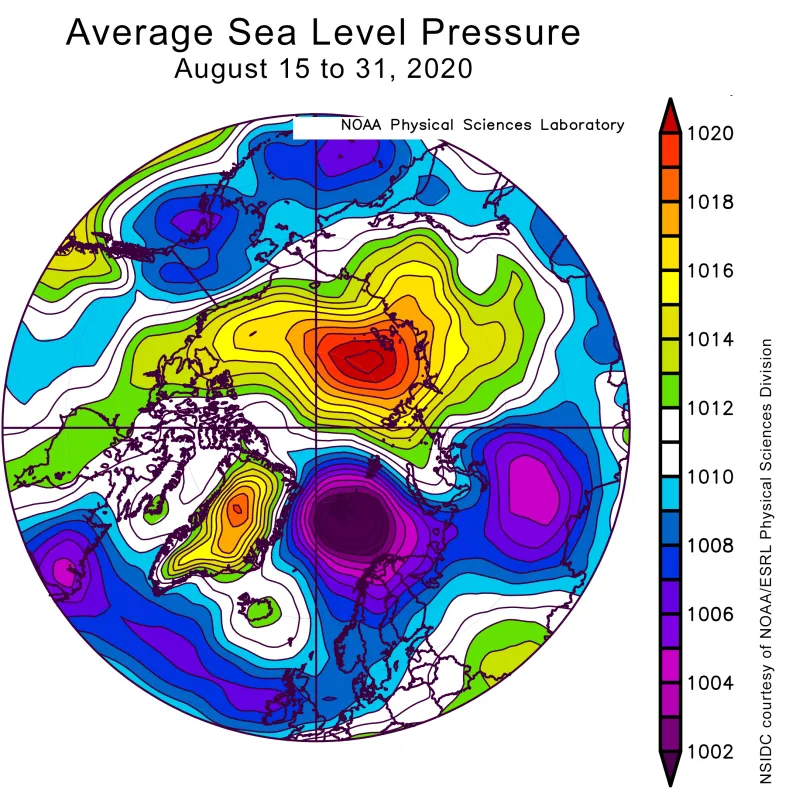

As assessed from August 15 to August 31, air temperatures at the 925 mb level (about 2,500 feet above sea level) were above average over much of the Arctic Ocean, continuing the basic pattern of warmth that prevailed through the first half of the month, most notably in the Kara Sea. Temperatures were below average over central Siberia (Figure 2b). The atmospheric circulation pattern shifted relative to the first half of the month to feature high pressure centered over the Laptev Sea and extending across the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas (Figure 2c). Low pressure has been the dominant feature of the Norwegian Sea region.

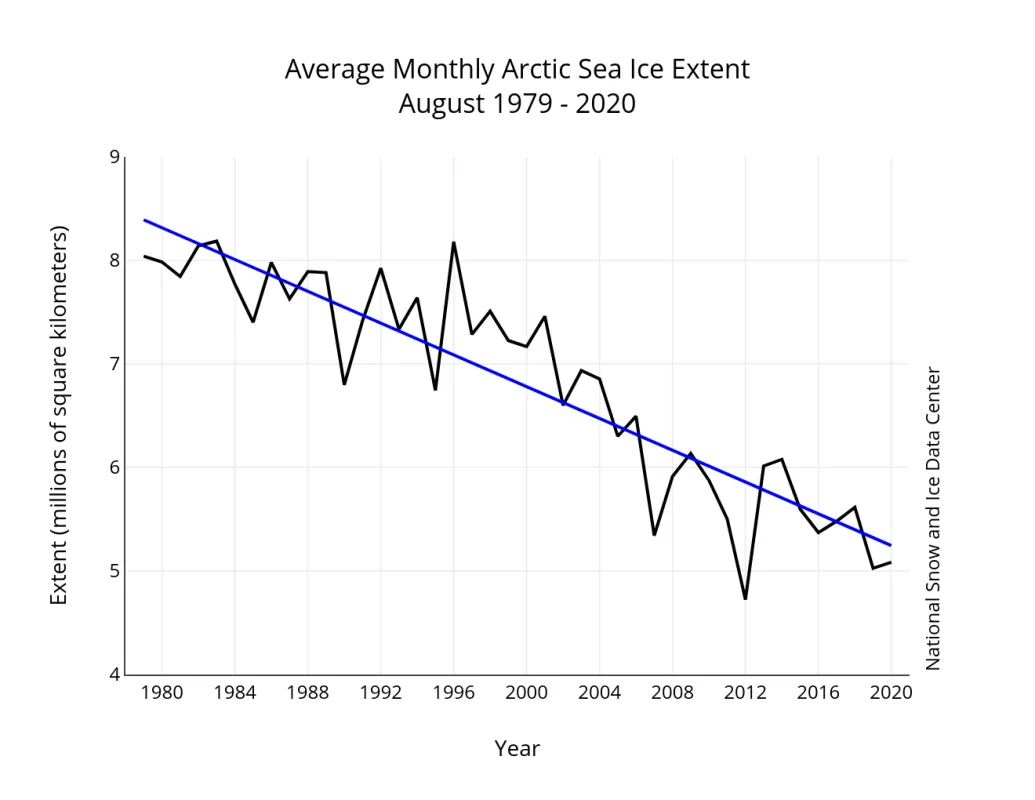

August 2020 compared to previous years

The average sea ice extent for August 2020 as a whole is 5.08 million square kilometers (1.96 million square miles), placing it third lowest in the 42-year satellite record. Including 2020, the linear rate of decline for August sea ice extent is 10.7 percent per decade. This corresponds to a trend of 76,800 square kilometers (29,700 square miles) per year, or about the size of New Hampshire, Vermont, and Massachusetts combined. Over the satellite record, the Arctic Ocean has lost about 3.15 million square kilometers (1.22 million square miles) of ice in August, based on the difference in linear trend values in 2020 and 1979. This is comparable in size to about twice the size of the state of Alaska.

Atlantification continues

As discussed in a recent paper in the Journal of Climate led by colleague Igor Polyakov of the University of Alaska, the process of “Atlantification” of the Arctic Ocean, first noted in the Barents Sea, is continuing, with significant effects on the sea ice cover during the winter season in the Eastern Eurasian Basin. The relatively fresh surface layer of the Arctic Ocean is underlain by warm, salty water that is imported from the northern Atlantic Ocean. The cold fresh surface layer, because of its lower density, largely prevents the warm, salty Atlantic waters from mixing upwards. However, the underlying Atlantic water appears to have moved closer to the surface in recent years, reducing the density contrast with the water above it. Recent observations show this warm water “blob,” usually found at about 150 meters (492 feet) below the surface, has shifted within 80 meters (263 feet) of the surface. This has resulted in an increase in the upward winter ocean heat flow to the underside of the ice from typical values of 3 to 4 watts per square meter in 2007 to 2008 to greater than 10 watts per square meter from 2016 to 2018. Polyakov estimates that this is equivalent to a two-fold reduction in winter ice growth.

Other recent news

The RV Polarstern, which has been supporting the Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate (MOSAiC) expedition, conducted an impromptu detour to the North Pole, taking advantage of fairly light ice conditions. Large openings in the sea ice were present north of Greenland, an area that would normally be very difficult to traverse. The United States’ medium-duty icebreaker Healy did not fare as well—a fire broke out in the engine compartment, and although it was quickly extinguished, the damage is extensive, and with the ship temporarily out of commission, a planned expedition to the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas has been cancelled.

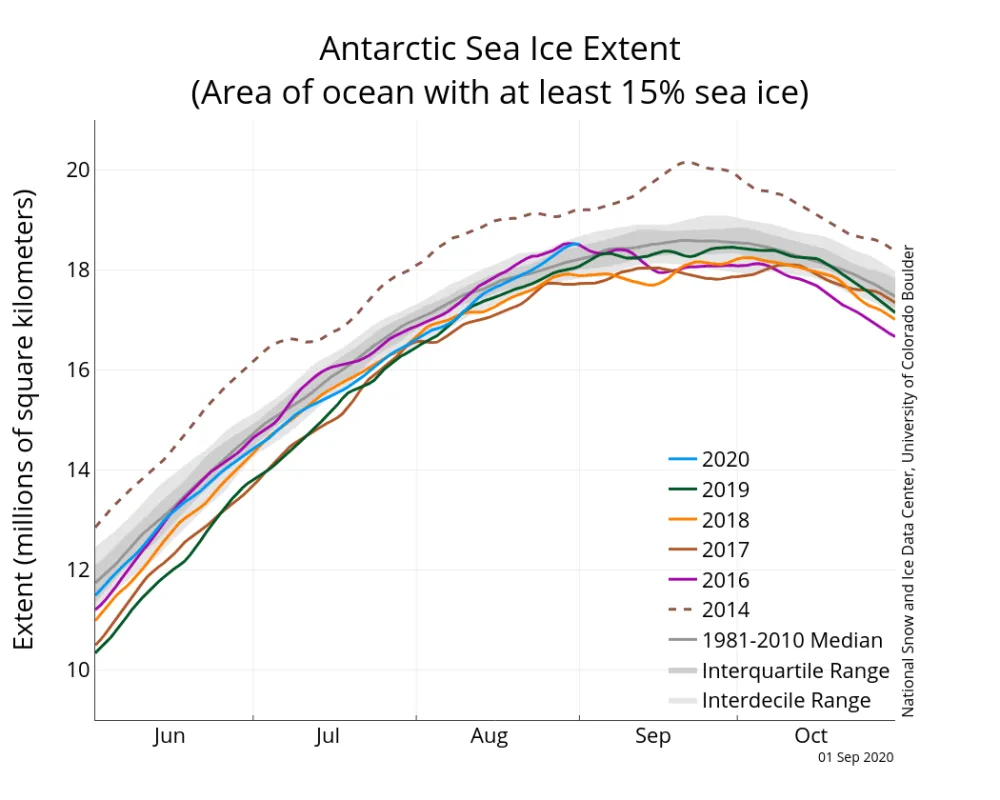

Antarctic sea ice: looking up down below

Antarctic sea ice growth in late winter has brought the ice extent substantially above average in late August for the first time in four years. Ice extent exceeded the 1981 to 2010 average over much of the Weddell Sea and off the Wilkes Land coast. A few areas of below-average extent persisted in the Davis Sea (south of Perth, Australia) and the northeastern Ross Sea. The cause appears to be persistent high air pressure in the western Weddell Sea and the Davis Sea that generate offshore cold winds on the eastern sides of the high-pressure areas. While Antarctica often has a trio of high pressure and low pressure areas surrounding it, for the second half of August there were just two such pairs.

Further reading

Polyakov, I. V., et al. 2020. Weakening of Cold Halocline Layer Exposes Sea Ice to Oceanic Heat in the Eastern Arctic Ocean. Journal of Climate, 33, 8107–8123, doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-19-0976.1.