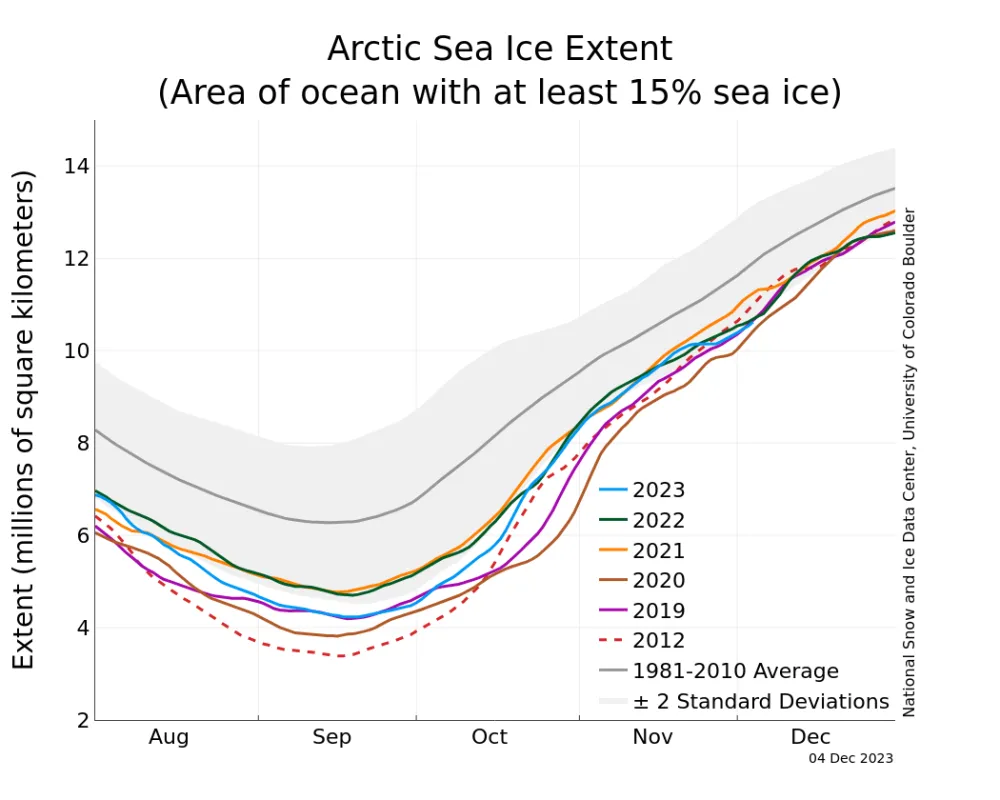

While autumn sea ice growth is in full swing, brief pauses are not unusual. Starting November 22, the ice growth stalled almost completely for five days as a series of storms guided an atmospheric river into the Arctic, transporting warm, moist air.

Overview of conditions

A November pause in ice growth occurred three times in the past: November 3 to 8, 2013; November 13 to 20, 2016; and now November 19 to 24, 2023. Thus, such events are rare but not unknown.

Conditions in context

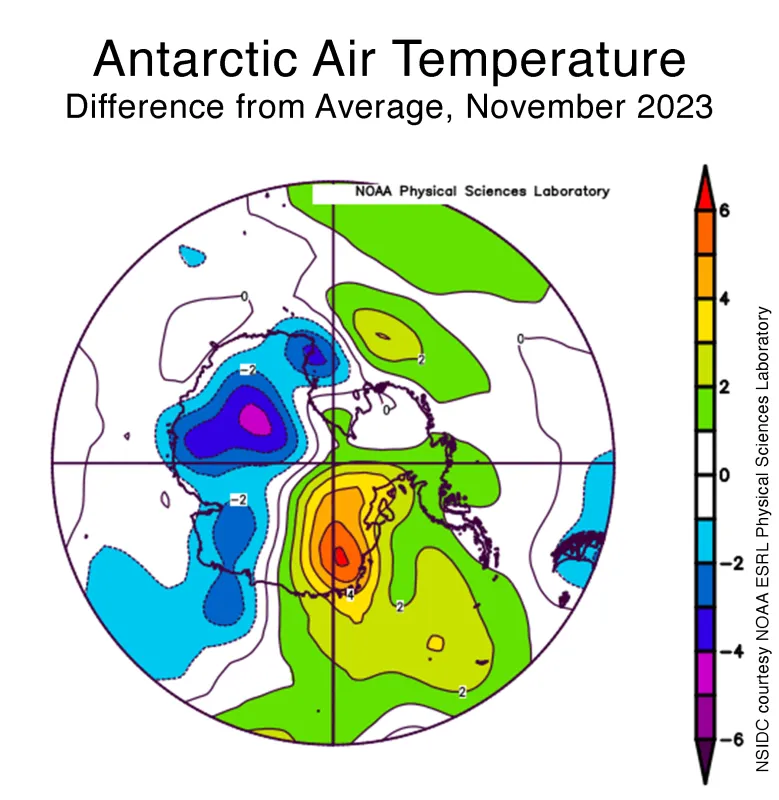

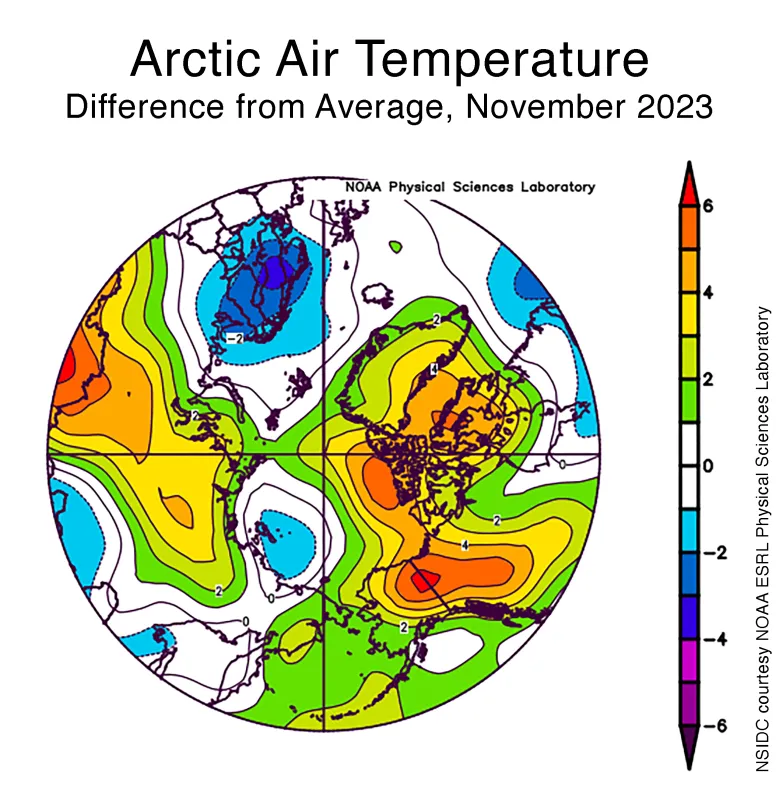

Air temperatures over the Arctic Ocean at the 925 millibar level (about 2,500 feet above the surface) in November were broadly similar to those seen in October, with mostly above average warmth in and around the Canadian Archipelago of 4 to 5 degrees Celsius (7 to 9 degrees Fahrenheit) (Figure 2a). Temperatures were modestly above average north of Greenland and stretching towards the Laptev and Kara Seas as well as the southern parts of the Beaufort Sea. The East Siberian Sea experienced near- to slightly-below average temperatures; temperatures were slightly below average over the Barents and Norwegian Seas.

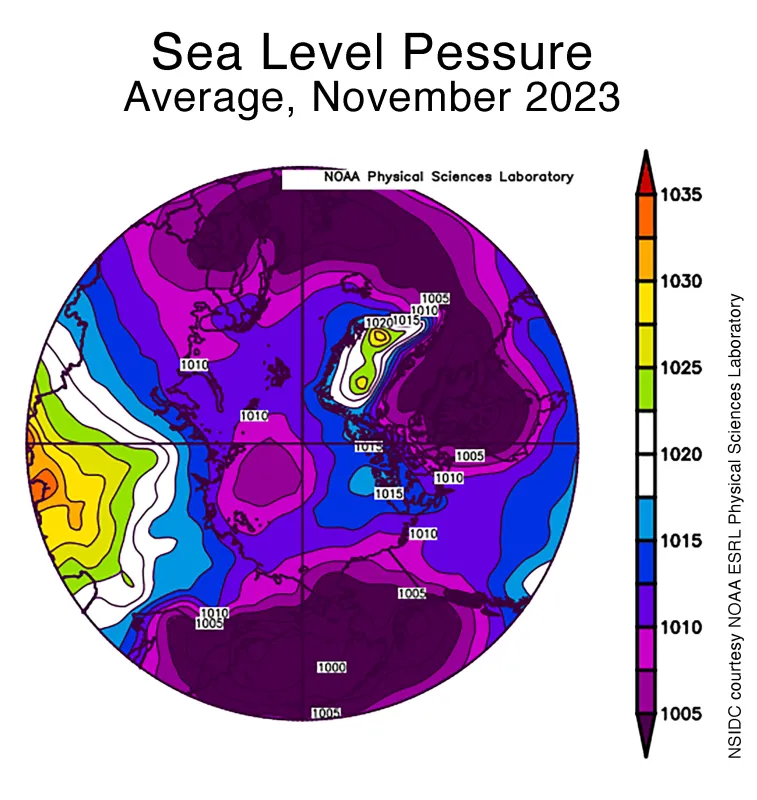

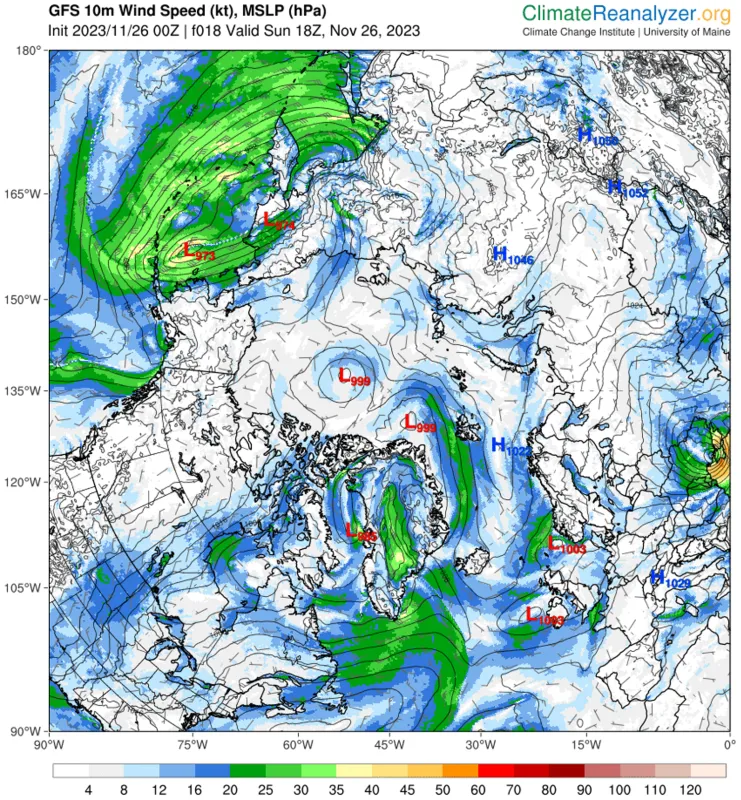

The atmospheric circulation for November featured fairly strong low pressure centered near the North Pole, with strong low pressure also dominating the north Atlantic, Eurasia, Baffin Bay, and North America (Figure 2b).

November 2023 compared to previous years

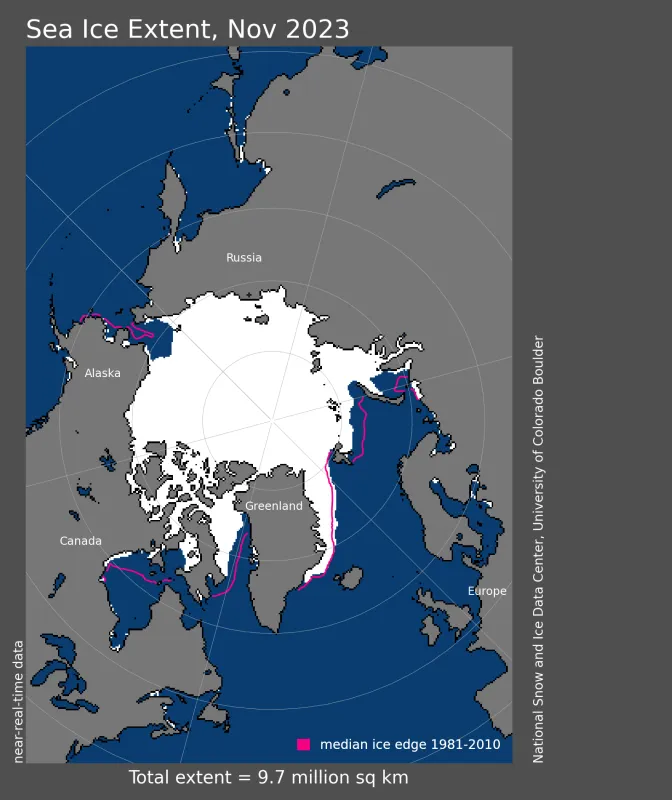

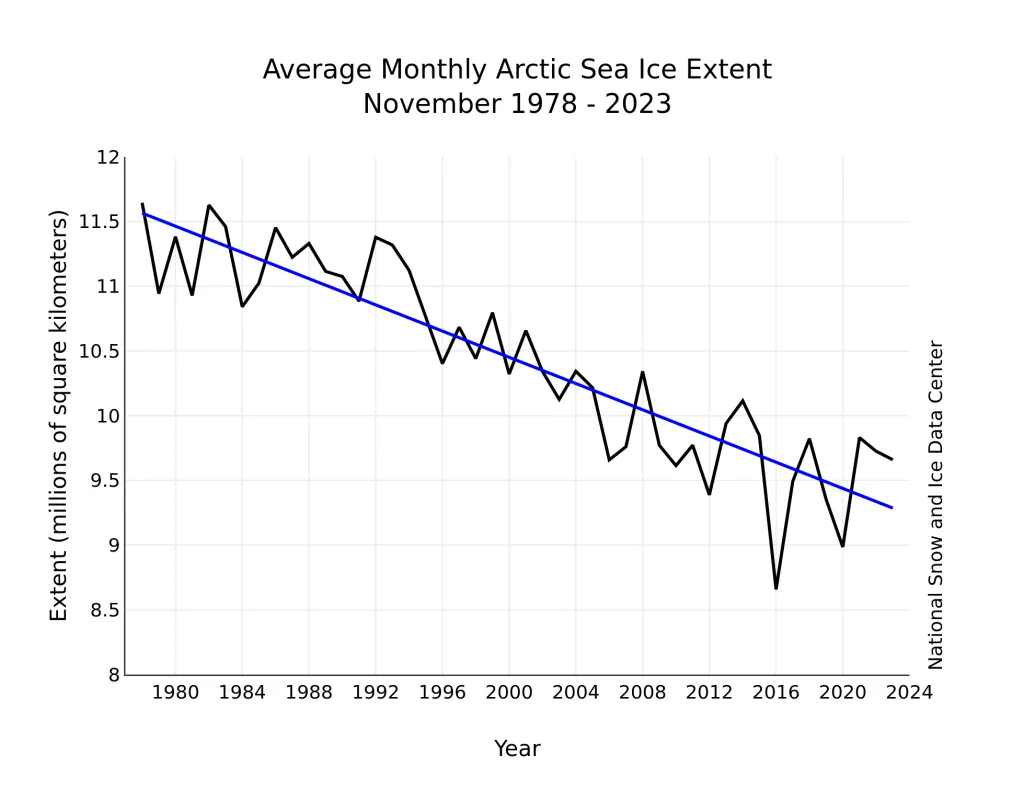

The downward linear trend in Arctic sea ice extent for November over the 45-year satellite record is 50,600 square kilometers (19,500 square miles) per year, or 4.7 percent per decade relative to the 1981 to 2010 average (Figure 3). Based on the linear trend, November has lost 2.28 million square kilometers (880,000 square miles) of ice since 1979. This is 1.3 times the size of Alaska.

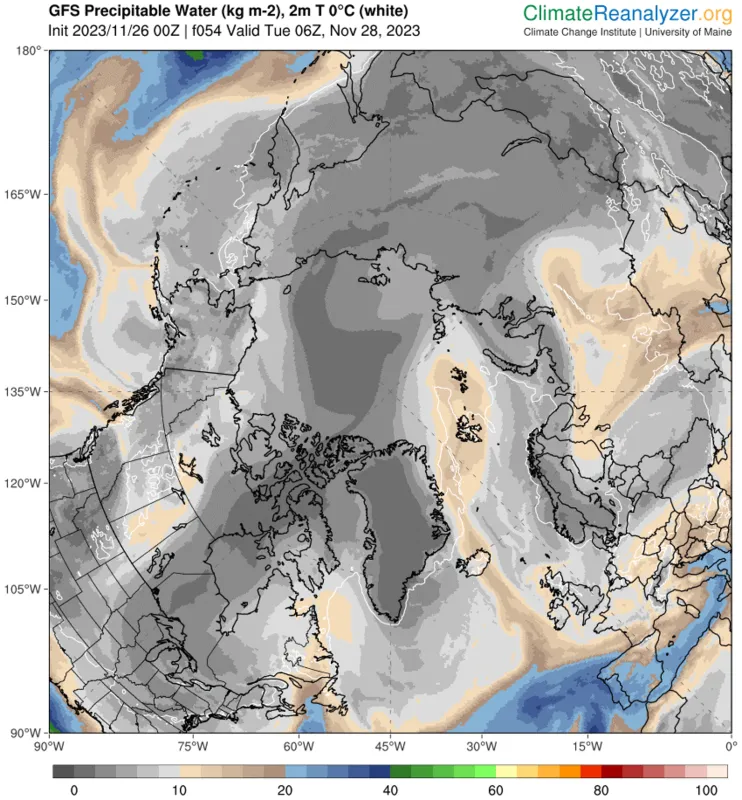

Rivers in the sky slow winter ice growth

From November 21 to 28, a series of three extratropical cyclones followed a common track from the northeast coast of Greenland eastward along the northern edge of the Barents, Kara, and Laptev Seas. As each storm moved into the Arctic Ocean, it merged with its predecessors, creating a persistent cyclonic (counter clockwise) wind regime. The first and third of these storms originated in the Icelandic Low region before migrating up the east side of Greenland. The second storm originated just north of Greenland. Simultaneously, a center of high pressure developed over the ice-free part of the Barents Sea, becoming especially strong on November 26 to 28.

This combination of persistent low pressure to the north and west of Svalbard and a high-pressure center to the southeast created a strong, persistent flow from the south of relatively warm and moist air from the North Atlantic Ocean toward Svalbard, which then turned eastward along the marginal ice zone. This is seen as an extension of an atmospheric river into the Arctic. Atmospheric rivers are long narrow corridors that carry a large amount of water vapor. A recent study suggests that atmospheric rivers lead to ice loss by transporting warm, moist air into the Arctic that can limit sea ice growth. This is consistent with the observed pause in seasonal ice growth in late November.

A wetter and warmer Arctic

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument on board NASA’s 21-year-old Aqua satellite has been taking twice-daily global measurements of the Earth’s temperature and humidity. When looking at these variables in the Arctic between 2003 to 2022, it was found that specifically in the fall months (September, October, November; SON) the near-surface air temperature and specific humidity has increased by 1.78 Kelvin and 0.26 grams of water vapor per kilogram of air since 2003 (column A). This warming and moistening is widespread over the Arctic Ocean and most pronounced in areas of sea ice loss. However, during the first 10 years of this record (column B) the sea ice loss was roughly three times as large as in the most recent 10 years (column C). The rapid loss of sea ice coverage in the first decade helped temperatures to rise more than 3.5 times the rate compared to the last decade. In the first decade the warming and moistening was widespread over the Arctic Ocean; however, in the most recent decade, this warming and moistening is more tightly coupled with smaller areas of sea ice loss. So, although the Arctic is becoming warmer with higher humidity over the past 20 years, these trends were driven by the rapid loss of sea ice coverage during the first 10 years of this record.

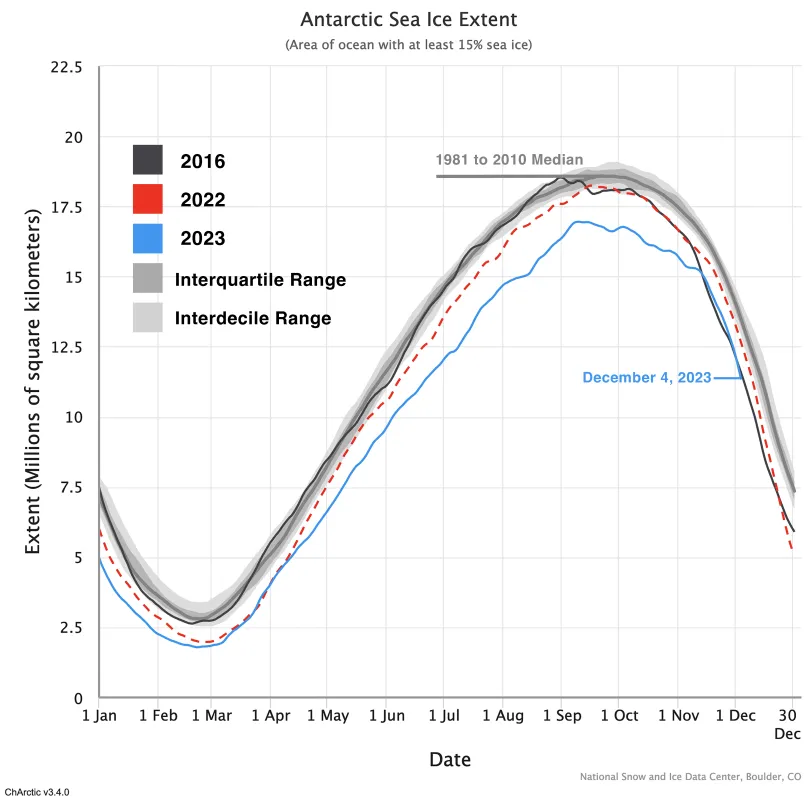

Antarctic sea ice: race to the bottom

The decline in Antarctic sea ice extent paused for a few days around November 9, which caused it to surpass the daily extents for November 2016 for most of the month, making it the second-lowest extent in the 45-year record. This was the first time that the 2023 extent was not the lowest in the record for each day since early May. However, the seasonal decline then picked up and closely followed the path of the record low 2016 daily extents, remaining slightly above but close to the 2016 daily values (Figure 6a). At month’s end, ice extent remained persistently low in the Weddell, Cosmonaut, and Ross Seas, but above the 1981 to 2010 average in the Bellingshausen and Amundsen Seas. Unusually warm conditions over the eastern Weddell Sea and strong offshore winds just to the east (Dronning Maud Land coast) caused retreat of ice along that coast and opened a wide shore polynya in that area (Figure 6b).

Further reading

Boisvert, L., C. Parker, and E. Valkonen. 2023. A warmer and wetter Arctic: Insights from a 20-years AIRS record. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 128, e2023JD038793. doi:10.1029/2023JD038793.

Fritts, R. 2023. Rivers in the sky are hindering winter Arctic sea ice recovery. Eos,104,13 March 2023. doi:10.1029/2023EO230098.

Zhang, P., G. Chen, M. Ting, and et al. 2023. More frequent atmospheric rivers slow the seasonal recovery of Arctic sea ice. Nature Climate Change, 13, 266–273. doi:10.1038/s41558-023-01599-3.

![The top row of maps shows trends for surface air temperature during Autumn (September, October, November [SON]), and the bottom row shows specific humidity during the same period. The top row of maps shows trends for surface air temperature during Autumn (September, October, November [SON]), and the bottom row shows specific humidity during the same period.](/sites/default/files/styles/article_image/public/images/Aerial%20photo/2023-Dec-ASINA-Figure5.png.webp?itok=jnK-IWC3)