After reaching the minimum on September 18, Arctic sea ice extent has been steadily increasing. With the passage of the equinox, the sun has set at the North Pole. September average ice extent ended up tying with 2010 for eleventh lowest in the satellite record.

Overview of conditions

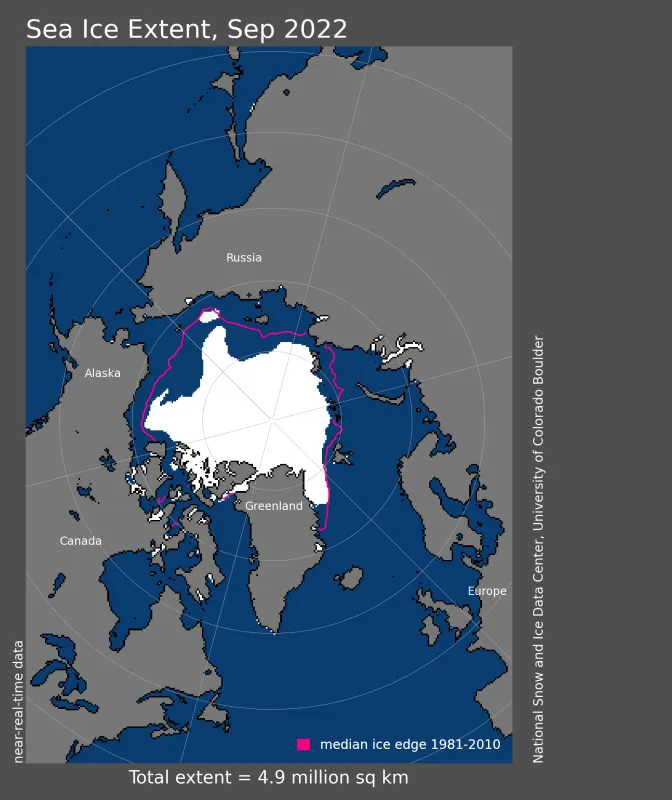

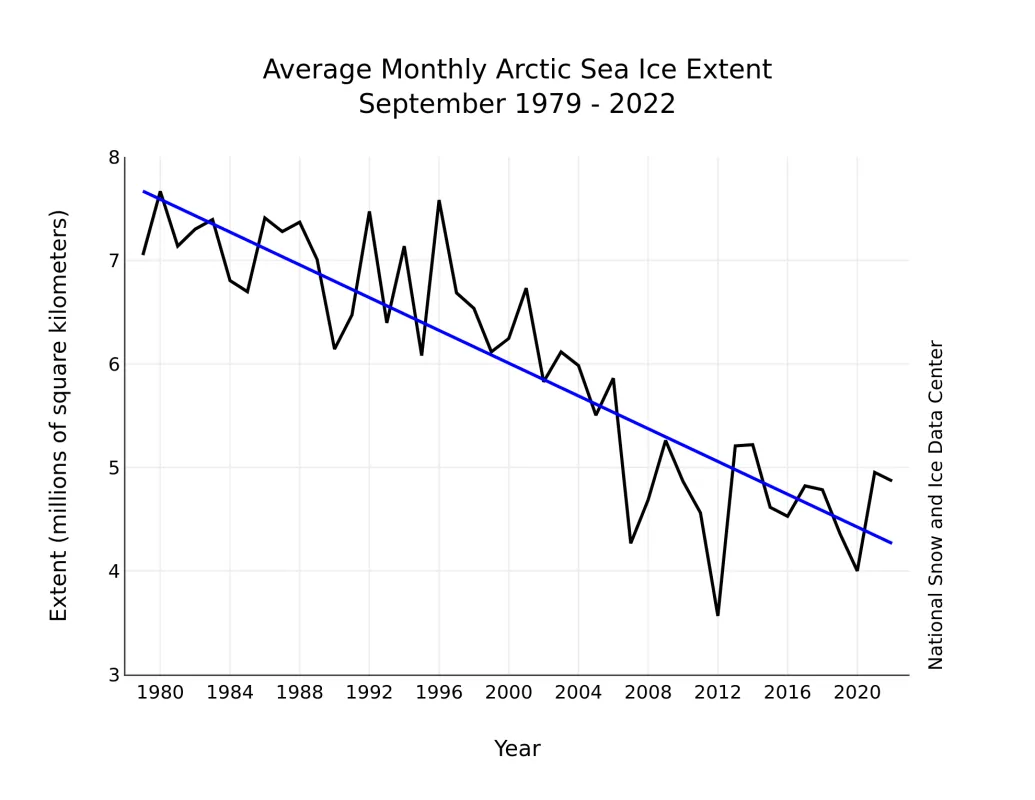

The September 2022 average Arctic sea ice extent was 4.87 million square kilometers (1.88 million square miles), tying with 2010 for eleventh lowest in the satellite record (Figure 1a). Extent was 1.54 million square kilometers (595,000 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 average and 1.30 million square kilometers (502,000 square miles) above the record minimum set in 2012. The annual minimum extent was reached on September 18 and the autumn freeze-up is now well underway.

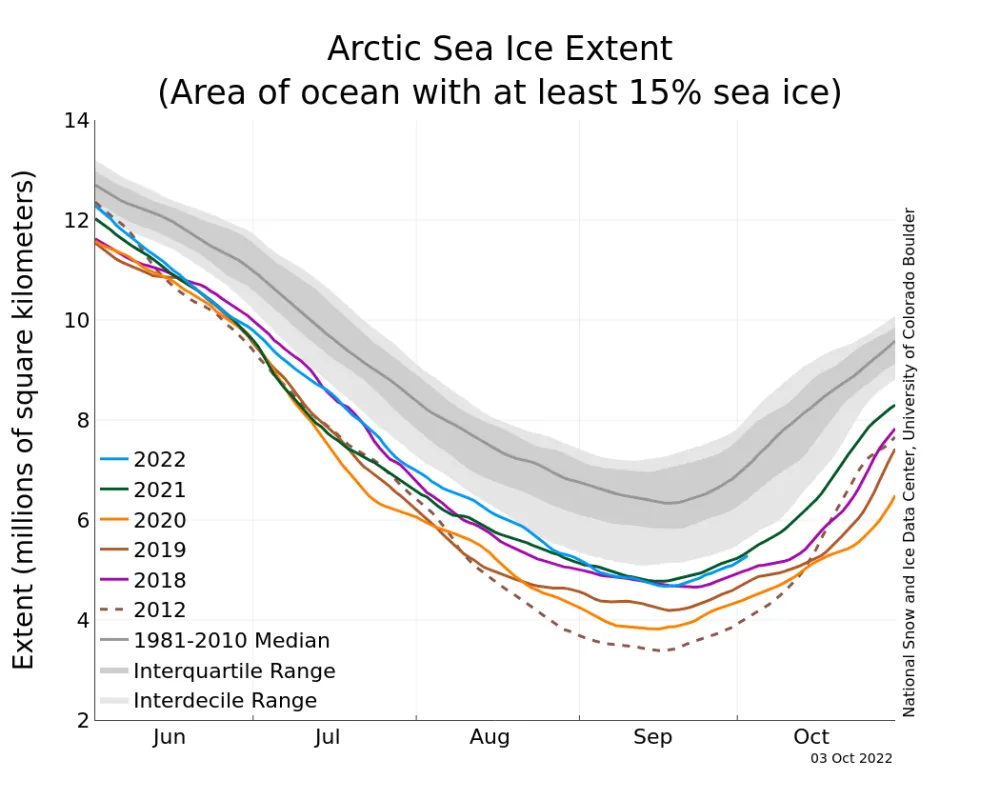

Ice extent declined at a faster than average rate from the beginning of the month until the minimum was reached on September 18 (Figure 1b). This resulted in a tie for the tenth lowest minimum daily extent in the satellite record. Extent was below average in all sectors of the Arctic Ocean, apart from the northern shore of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, where ice is almost invariably pushed up against the coast by winds and ocean currents. A tongue of ice continued to extend southward in the East Siberian Sea, and a portion of ice floes broke away from the main pack ice off the tip of that tongue. An open water passage has nevertheless persisted along the Northern Sea Route. The Northwest Passage has started to freeze up, particularly the northern route through Parry Channel, but much of the Canadian Archipelago remained essentially ice free through the end of the month.

Conditions in context

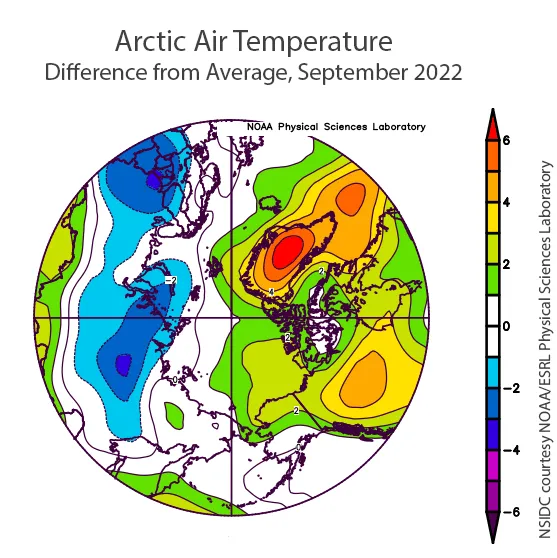

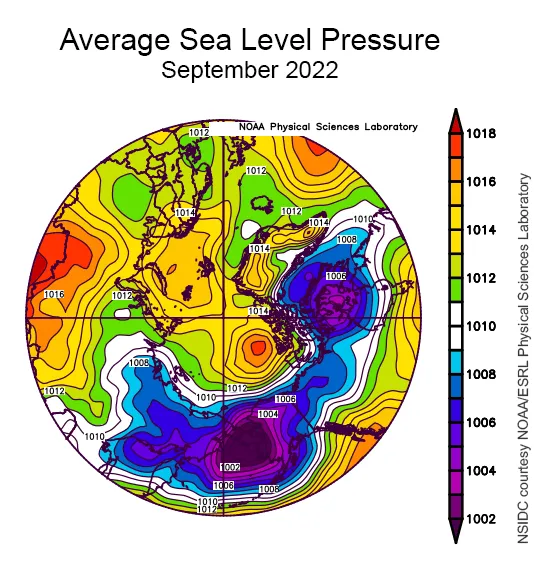

Air temperatures during September at the 925 millibar level (approximately 2,500 feet above the surface) were above average over the North American side of the Arctic and near average or below average over most of the Eurasian side (Figure 2a). Averaged sea level pressure for September featured low pressure extending across Eurasia, Alaska, and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, with high pressure over the central Arctic Ocean, notably north of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago (Figure 2b). The low pressure over Alaska reflects the passage of an extremely strong storm during the middle of the month that caused extensive damage and flooding to the town of Nome and surrounding areas.

September 2022 compared to previous years

The downward linear trend in September sea ice extent over the 44-year satellite record is 79,100 square kilometers (30,500 square miles) per year, or 12.3 percent per decade relative to the 1981 to 2010 average. Based on the linear trend, since 1979, September has lost 3.59 million square kilometers (1.39 million square miles). This is equivalent to about twice the size of Alaska.

Summer 2022 in review

The summer 2022 melt season had some noteworthy highlights. Extent loss was less extreme than recent years through much of the summer; for the first time since 2014, extent briefly sat within the 1981 to 2010 lower interdecile range. However, late season ice loss was strong, pushing the September average to eleventh lowest in the passive microwave satellite record. No region of the Arctic was extreme in terms of how far north the ice edge retreated, though compared to average conditions, the ice edge was quite far north in the Laptev and Chukchi Seas. Surface melt onset was also variable, with earlier-than-average melt along the Siberian coast, particularly in the Kara and Barents Seas, but later-than-average melt in much of the central Arctic Ocean.

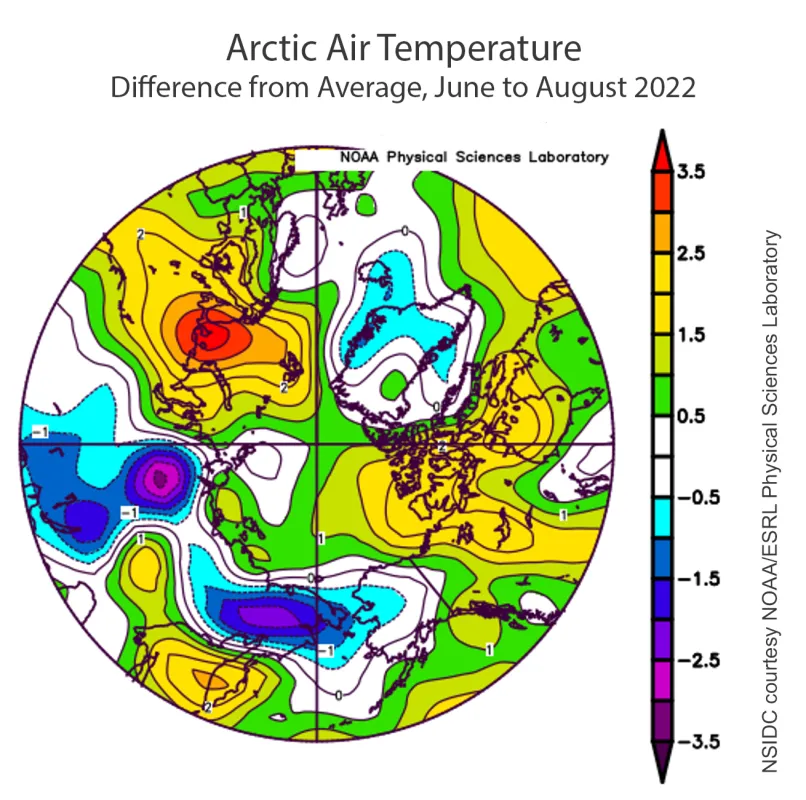

Air temperatures at the 925 millibar level (about 2,500 feet above sea level) were above average over much of the Arctic Ocean, but not as extreme as in many recent summers. Much of the Arctic Ocean experienced summer (June, July, August) temperatures 1 to 3 degrees Celsius (2 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit) above average (Figure 4a). Only in parts of the Barents Sea did 2022 summer air temperatures reach up to 4 degrees Celsius (7 degrees Fahrenheit) above average. In the southern Chukchi and northern Bering Seas, temperatures were 1 degree Celsius (2 degrees Fahrenheit) below average.

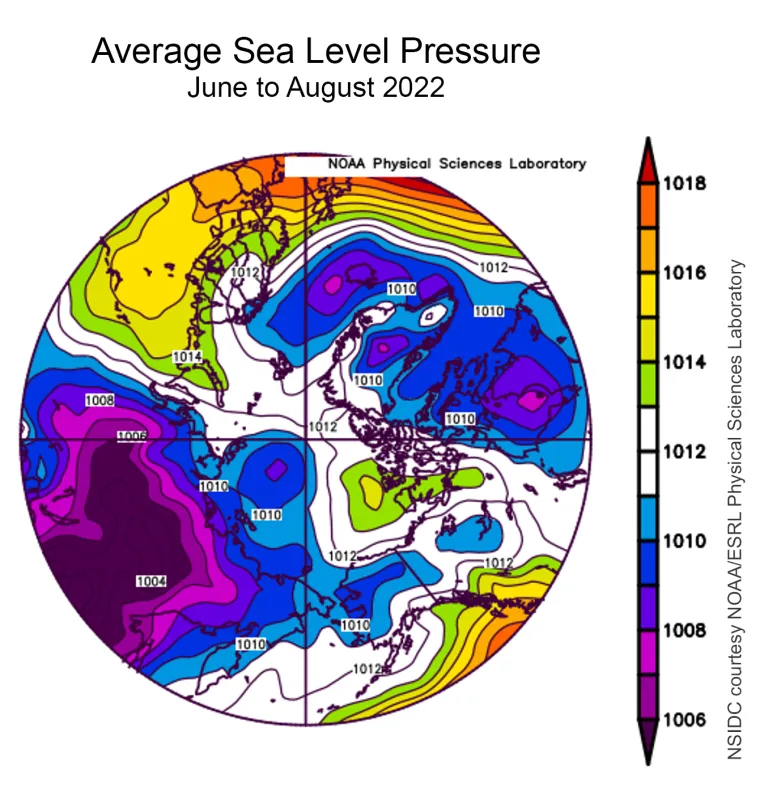

During June through August, average sea level pressure was low over much of the Siberian side of the Arctic, as well as over eastern Canada, and east of Greenland, with a small and weak Beaufort Sea High that primarily manifested itself in June (Figure 4b). Summer-averaged pressure gradients were slack, particularly in July and August, albeit with intermittent stronger gradients caused by passing weather systems. Weak pressure gradients resulted in relatively weak surface winds and sea ice circulation through much of the summer.

Of particular note was the formation of polynyas north of the Kara Sea, at about 87 degrees North latitude. These started to form in early July and were observed intermittently through the end of August. These unusual polynyas likely opened at least in part because of divergent ice motion, but their formation and general persistence is also an indication of thin, young, and uncompacted ice. It is also possible that deep ocean waters were churned toward the surface as currents flowed over the Lomonosov Ridge beneath some of the polynya areas.

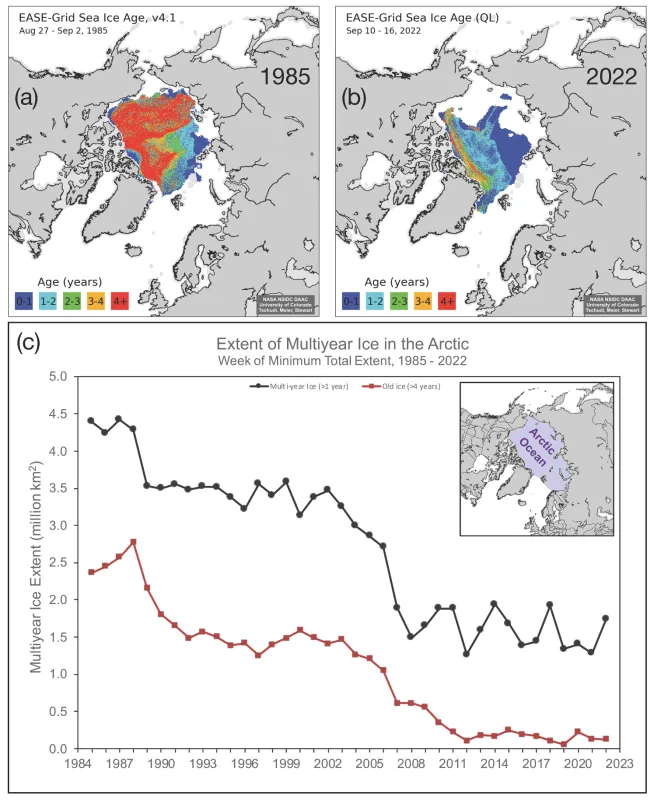

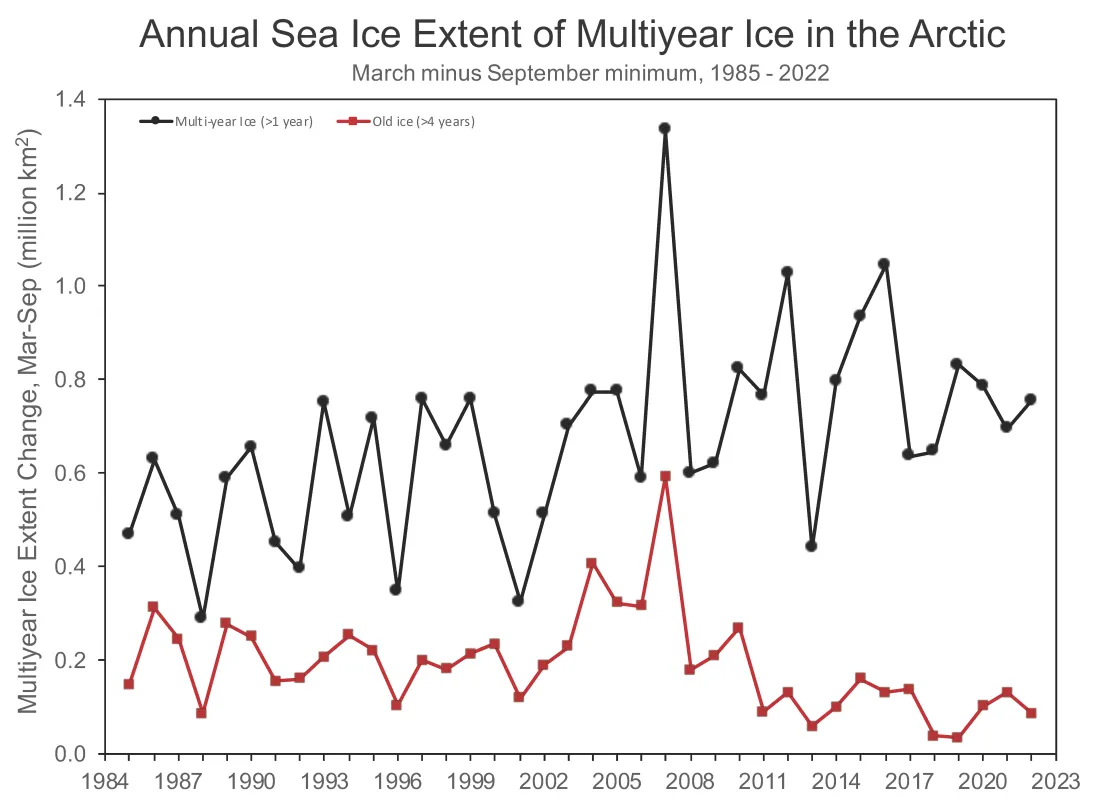

The distribution of sea ice age at the end of summer 2022 shows a dominance of first and second-year ice (Figure 4c). Some of this second-year ice extends south into the East Siberian Sea and is one reason why the Northern Sea Route maintained ice until later in the summer. A thin ribbon of old ice (3 to 4 and 4+ years age) extends along the northern shore of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The summertime loss of the multiyear ice has generally increased since the mid 1980s, but with large variations from one summer to the next (Figure 4d). The 4+ year-old ice shows less summertime change, especially since 2012, because so little of that ice remains in the Arctic. The most notable feature in both ice age classes is the large spike in loss during the 2007 summer.

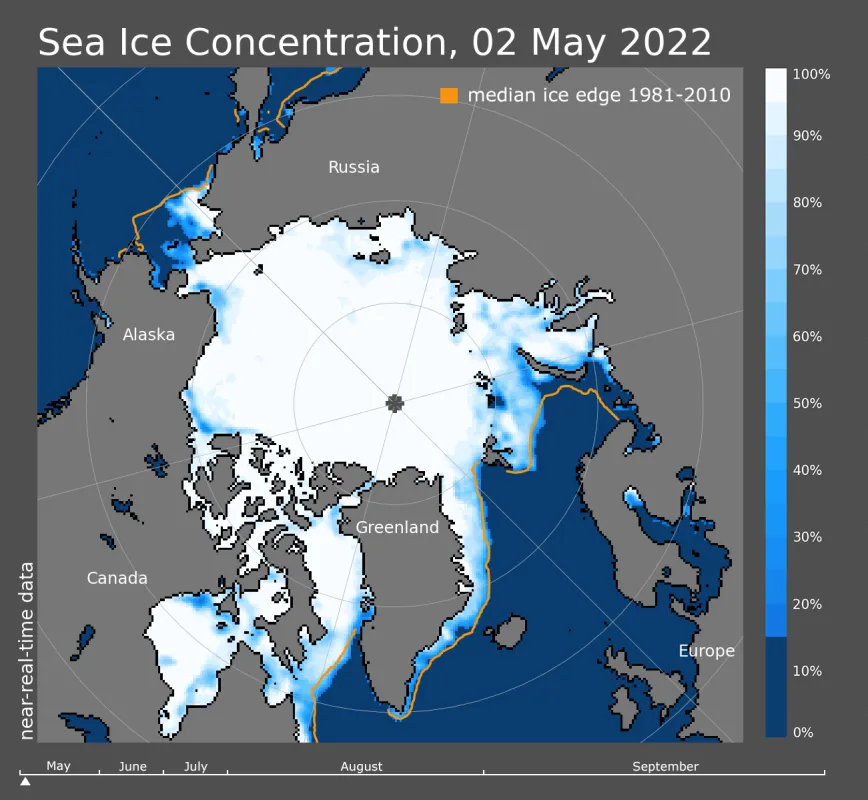

The evolution of sea ice concentration during the 2022 melt season is presented in an animation, which begins on May 2 and ends at the sea ice minimum on September 18 (Figure 4f). Rapid early loss is noticeable in the Kara Sea with large retreats also occurring in the Laptev and Beaufort Seas. By August, a tongue of somewhat older and thicker ice is left behind in the East Siberian Sea. Retreat was generally ahead of the average date for ice extent through the summer. Also shown is the unusually persistent low sea ice concentration in the high Arctic north of the Severnaya Zemlaya islands, eventually leading to the opening of two high-latitude polynyas in late August into early September. Melt events are shown as brief drops in concentration, but the regions around the polynyas remained low throughout the second half of the summer.

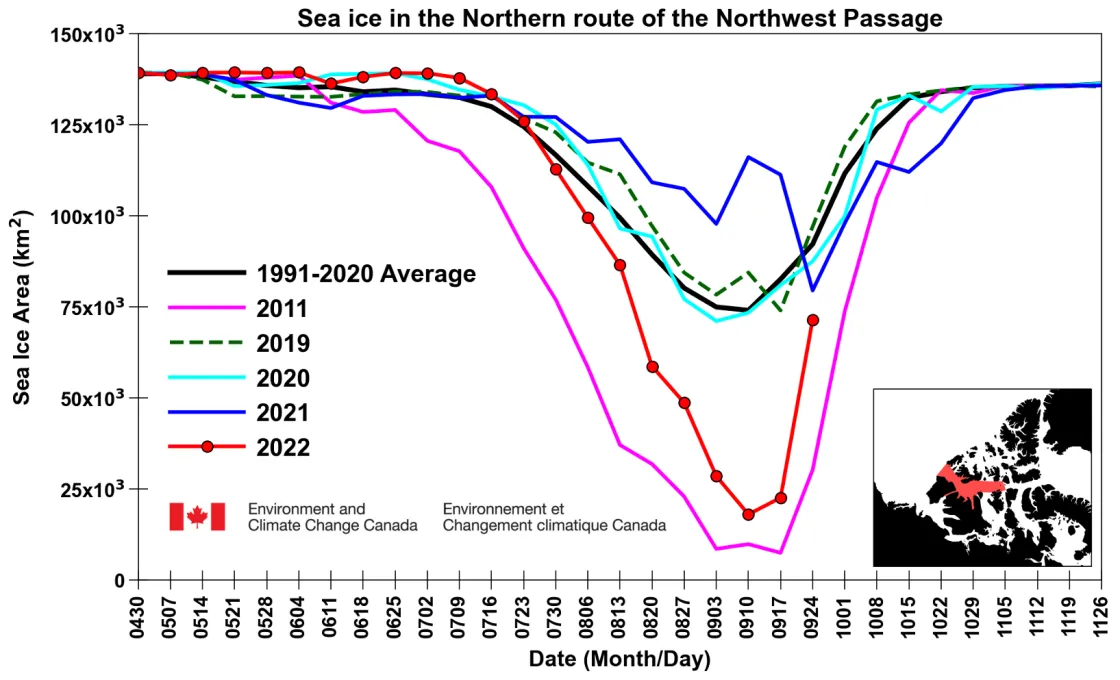

The Northwest Passage (NWP)—a shortcut between Europe and Asia through the channels of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago—was the dream of explorers and financiers for centuries. The southern NWP route was first navigated by Roald Amundsen over three summers, 1905 to 1908. In recent years, his circuitous route, winding through narrow and shallow channels, has often opened for at least part of the summer. However, even in recent years, the more direct northern route through Parry Channel, with wide and deep channels more suitable for shipping, has remained choked with ice. This is partly because of an influx of thick, multiyear ice into the channel from the Arctic Ocean to the north. This year the northern route largely opened. While operational analysis showed the region with 10 to 80 percent ice cover, high resolution maps of the ice cover, indicated a continuous path through open water starting in late August until mid-September. Overall, the ice area in the northern route reached the fourth lowest in the 55-year record of Canadian Arctic sea ice conditions analyzed by the Canadian Ice Service; the NWP information was provided by Steve Howell of Environment and Climate Change Canada (Figure 4e).

Top ten lowest sea ice extents in northern route of the Northwest Passage

| Rank | Year | Sea Ice Area (km2) | Date |

| 1 | 2011 | 7,506 | 2011-09-19 |

| 2 | 2015 | 12,695 | 2015-09-14 |

| 3 | 2012 | 14,613 | 2012-10-01 |

| 4 | 2022 | 18,050 | 2022-09-12 |

| 5 | 2010 | 18,583 | 2010-09-06 |

| 6 | 2008 | 28,745 | 2008-09-08 |

| 7 | 1998 | 33,663 | 1998-09-28 |

| 8 | 1999 | 36,608 | 1999-09-13 |

| 9 | 2007 | 36,703 | 2007-09-10 |

| 10 | 2016 | 44,936 | 2016-08-22 |

The view down south

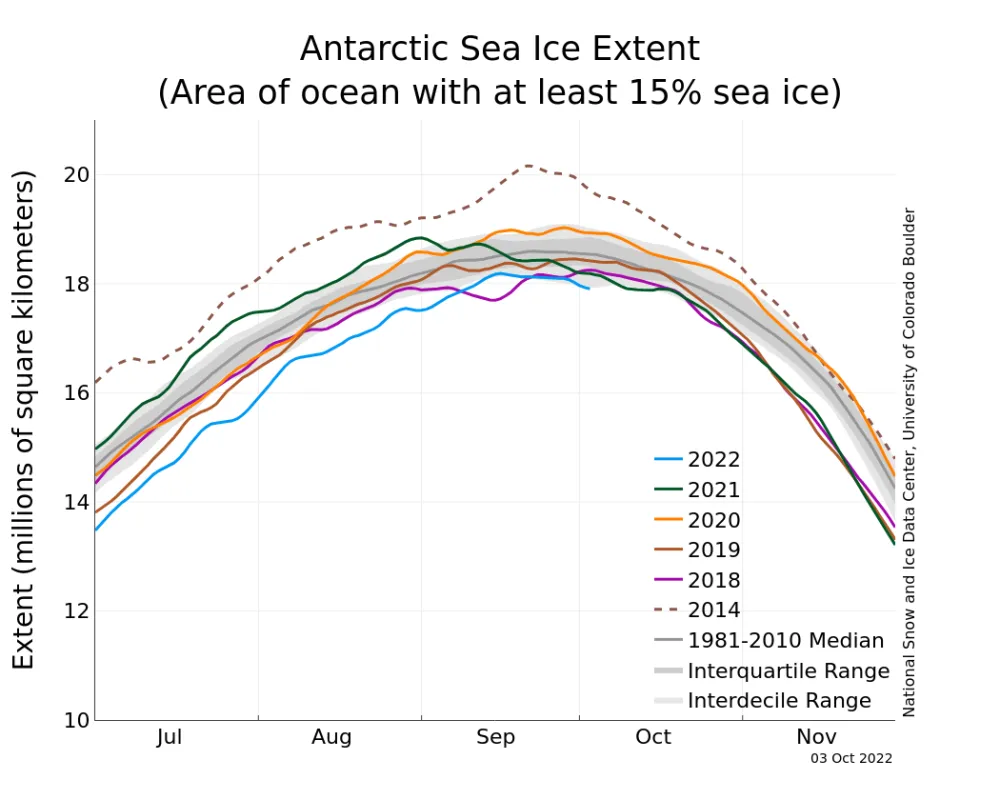

As the Arctic makes its journey into autumn, Antarctic sea ice extent is nearing its winter maximum. On September 16, extent stood at 18.19 million square kilometers (7.02 million square miles), which may represent the seasonal maximum. However, extent may yet rise above that value. After record and near-record low extent earlier in the year, late ice growth increased the extent within the inter-decile range by mid-September.

Antarctic sea ice extent has exhibited extreme interannual variability with record highs and record lows within the past decade. There is also strong regional variability, with some areas showing long-term trends of ice loss, with others showing gains. One region with a notable downward trend in extent is the Bellingshausen Sea, west of the Antarctic Peninsula. The Peninsula region has also experienced a strong multi-decade warming trend, which has resumed after a decade-long hiatus. One factor in these changes is a strengthening of the Amundsen Low the brings southward winds to the region, which raise air temperatures and compact the ice. A new study by Dalaiden et al. suggests that this Amundsen Low strengthening is caused by an anthropogenic forcing, and a coupling to the general temperature pattern and trends in the Pacific Ocean.

Update

On October 5, 2022, the Sea Ice Today team decided to add the animation of sea ice loss through the melt season and corresponding text (Figure 4f).

References

Dalaiden, Q., A. P. Schurer, M. C. Kirchmeier-Young, H. Goosse, and G. C. Hegerl, G. 2022. West Antarctic surface climate changes since the mid-20th century driven by anthropogenic forcing. Geophysical Research Letters, 49, e2022GL099543. doi:10.1029/2022GL099543.

Tschudi, M., W. N. Meier, J. S. Stewart, C. Fowler, and J. Maslanik. 2019. EASE-Grid Sea Ice Age, Version 4 [Data Set]. Boulder, Colorado USA. NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center. doi:0.5067/UTAV7490FEPB. Date Accessed 10-04-2022.

Tschudi, M., W. N. Meier, and J. S. Stewart. 2019. Quicklook Arctic Weekly EASE-Grid Sea Ice Age, Version 1 [Data Set]. Boulder, Colorado USA. NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center. doi:10.5067/2XXGZY3DUGNQ. Date Accessed 10-04-2022.