By Agnieszka Gautier

As Arctic sea ice melts to reveal the open ocean underneath, fragile coastlines become vulnerable to bigger waves from storms, leading to accelerated erosion that impacts people and wildlife.

Like a layer of plastic wrap covering a bowl of soup, sea ice keeps the churning ocean underneath it from splashing up against the coast. A thick layer of sea ice absorbs the power of big waves, preventing them from slamming into beaches and sea cliffs. But as sea ice melts and recedes away from shore, the ocean can wear away coastlines and flood seaside villages.

Unlike shorelines in the mid-latitudes, Arctic shorelines have frozen soil, known as permafrost. With higher temperatures in the summer, these soils are thawing, making Arctic coasts especially sensitive to erosion. Warming water and sea level rise compound the issue further as bigger waves pound the coasts.

Unfortunate encounters

Two events often collide in the autumn in the Arctic: the strongest storms and lowest sea ice extent. After a summer of sea ice melt, with large areas of open water, large storms can do considerable damage and contribute to shoreline erosion and terrestrial habitat loss.

For example, in September 2022, remnants of Typhoon Merbok battered Alaska’s western coast with hurricane-force winds, forcing evacuations, uprooting buildings, carving out new shores, and surging three to seven feet of water along 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) of coastline (an equivalent distance as from New York City to Tampa, Florida). For many communities, the impact from damage to infrastructures was immediate. However, as these communities also rely on subsistence living, the loss of resources from the land—including harvests and disruption of animal habitats—left several residents vulnerable without stocks for the winter.

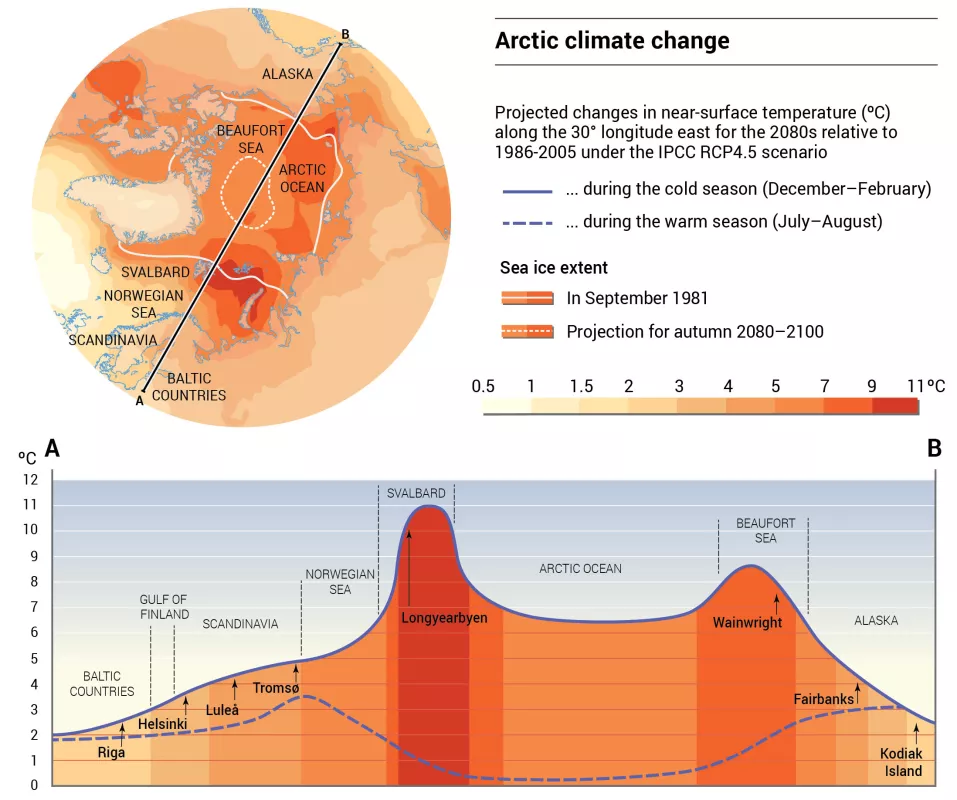

The not-so-permanent permafrost

The Arctic’s soil, once frozen all year round, now faces several months of thaw, with some regions thawing faster and more substantially than others. Since the 1990s, temperatures in the Arctic have been increasing at roughly 0.6°C (1°F) per decade—twice the rate of the global average. The Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme report states that, from 1971 to 2019, the rate of Arctic warming was three times as fast as the global average. Another study suggests a four-fold warming. Known as Arctic Amplification, the result is an observed downward trend of Arctic sea ice decline with some aggressive estimates showing a summer free of sea ice as early as 2035. With less sea ice preventing big waves crashing against the shores, coastal erosion increases.

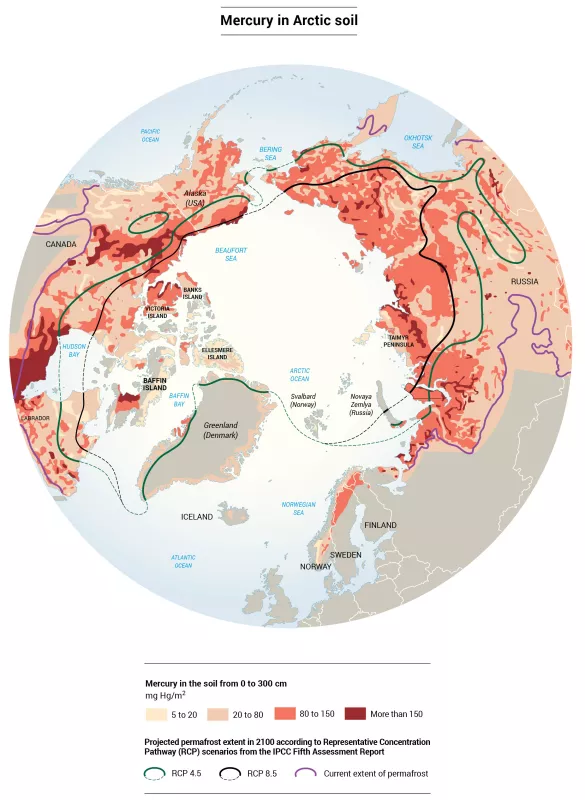

Warmer Arctic temperatures are also thawing permafrost, turning once frozen-solid land into soft, wet soil that crumbles more easily with wave attacks. Permafrost thaw also releases once-frozen greenhouse gases into nearby waters and the atmosphere, feeding further warming. Some estimates state that permafrost zones store about 1,700 billion metric tons of carbon—both in methane and carbon dioxide form—about twice the current total within the atmosphere. Another byproduct is the release of once-frozen mercury into soil and nearby waters, polluting the food chain.

How much and how fast

In Alaska, entire villages are already facing the need for relocation from coastal erosion. Together, thawing permafrost and waves erode the Arctic coastline at an average rate of 0.5 meters (1.6 feet) per year. In northern Alaska, the rates are 1.4 meters (4.6 feet) per year, with some sections, like Drew Point, Alaska, eroding much as 20 meters (66 feet) per year.

In other regions around the Arctic, a strong correlation between erosion and thawing temperatures have been reported in the Mackenzie Delta region of the Canadian Beaufort Sea and in Muostakh Island of the Laptev Sea, where erosion rates range between 10 and 20 meters (33 and 66 feet) per year.

Another study from February 2022 suggests that erosion may double in the Arctic by the end of the twenty-first century. As scientists learn more about the timing and magnitude of coastal erosion in the Arctic, communities can develop necessary mitigation and adaptation resources.

References

Gibbs, A. E. and B. M. Richmond. 2015. National assessment of shoreline change—Historical shoreline change along the north coast of Alaska, U.S.–Canadian border to Icy Cape. US Geological Survey Open-File Report 2015, 1048, 96 p. https://dx.doi.org/10.3133/ofr20151048

Nielsen, D. M., M. Dobrynin, J. Baehr, S. Razumov, and M. Grigoriev. 2020. Coastal erosion variability at the southern Laptev Sea linked to winter sea ice and the Arctic Oscillation. Geophysical Research Letters, 47, e2019GL086876. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL086876

Nielsen, D. M., P. Pieper, A. Barkhordarian, et al. 2022. Increase in Arctic coastal erosion and its sensitivity to warming in the twenty-first century. Nature Climate Change. 12, 263–270. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01281-0

Rantanen, M., A. Y. Karpechko, A. Lipponen, K. Nordling, O. Hyvärinen, K. Ruosteenoja, T. Vihma, and A. Laaksonen. 2022. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Nature Communications Earth & Environment, 3, 168. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00498-3