Daily Arctic sea ice extents for May 2016 tracked two to four weeks ahead of levels seen in 2012, which had the lowest September extent in the satellite record. Current sea ice extent numbers are tentative due to the preliminary nature of the DMSP F-18 satellite data, but are supported by other data sources. An unusually early retreat of sea ice in the Beaufort Sea and pulses of warm air entering the Arctic from eastern Siberia and northernmost Europe are in part driving below-average ice conditions. Snow cover in the Northern Hemisphere was the lowest in fifty years for April and the fourth lowest for May. Antarctic sea ice extent grew slowly during the austral autumn and was below average for most of May.

Overview of conditions

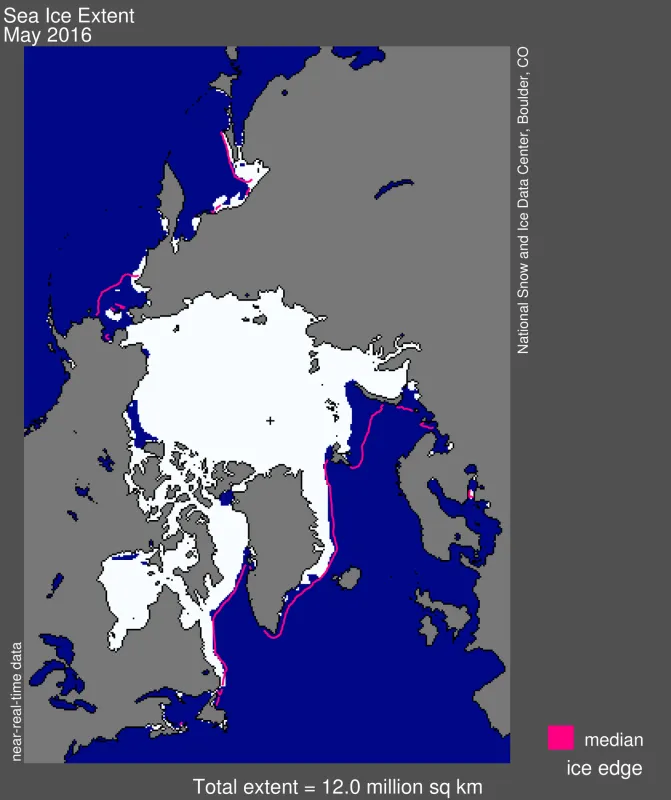

May 2016 set a new record low for the month for the period of satellite observations, at 12.0 million square kilometers (4.63 million square miles), following on previous record lows this year in January, February, and April. May’s average ice extent is 580,000 square kilometers (224,000 square miles) below the previous record low for the month set in 2004, and 1.39 million square kilometers (537,000 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 long-term average.

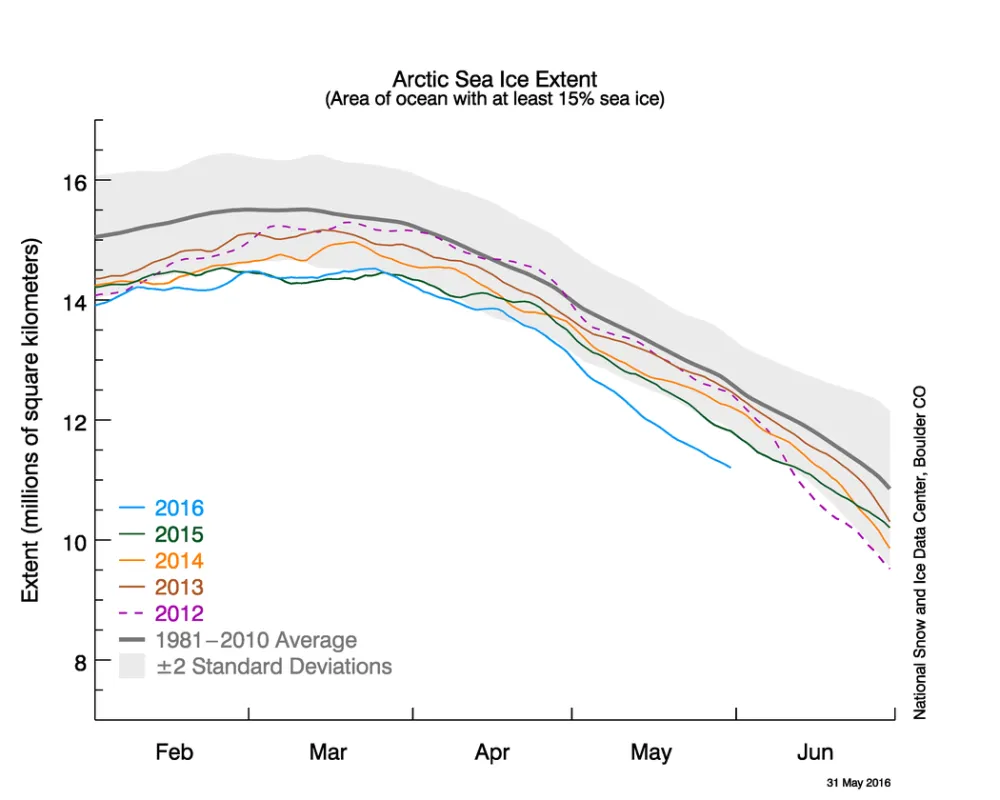

During the month, daily sea ice extents tracked about 600,000 square kilometers (232,000 square miles) below any previous year in the 38-year satellite record. Daily extents in May were also two to four weeks ahead of levels seen in 2012, which had the lowest September extent in the satellite record. The monthly average extent for May 2016 is more than one million square kilometers (386,000 square miles) below that observed in May 2012.

Sea ice extent remains below average in the Kara and Barents seas, continuing the pattern seen throughout winter 2015 and 2016. Sea ice also remains below average in the Bering Sea and the East Greenland Sea. In the Beaufort Sea, large open water areas have formed near the coast and ice to the north is strongly fragmented due to wind-driven divergence. The opening began in February, continued through March, and greatly expanded in April.

Conditions in context

The average ice loss during May 2016 was 61,000 square kilometers (23,600 square miles) per day. This was faster than the 1981 to 2010 long-term average rate of decline of 46,600 square kilometers (18,000 square miles) per day. May air temperatures at the 925 hPa level were 2 to 3 degrees Celsius (4 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit) above the 1981 to 2010 average across most of the Arctic Ocean, with localized higher temperatures in the Chukchi Sea (4 to 5 degrees Celsius or 7 to 9 degrees Fahrenheit) and in the Barents Sea (4 degrees Celsius or 7 degrees Fahrenheit). Air pressure patterns were not particularly unusual, but two areas of southerly winds in northern Europe and Alaska pushed higher than average temperatures into the Arctic Ocean, producing hot spots noted above and generally above-average temperatures across the Arctic. Only over central Siberia were temperatures lower than the 1981 to 2010 average.

May 2016 compared to previous years

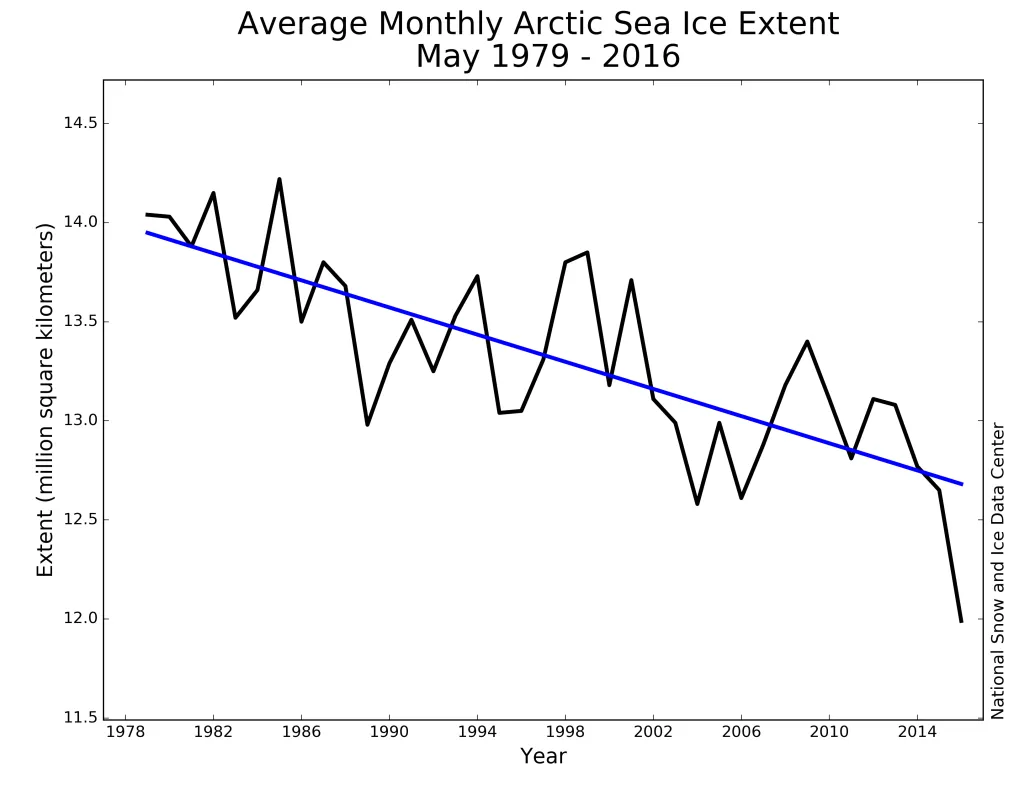

Through 2016, the rate of decline for the month of May is 34,000 square kilometers (13,000 square miles) per year, or 2.6 percent per decade.

Thickness in the Beaufort Sea

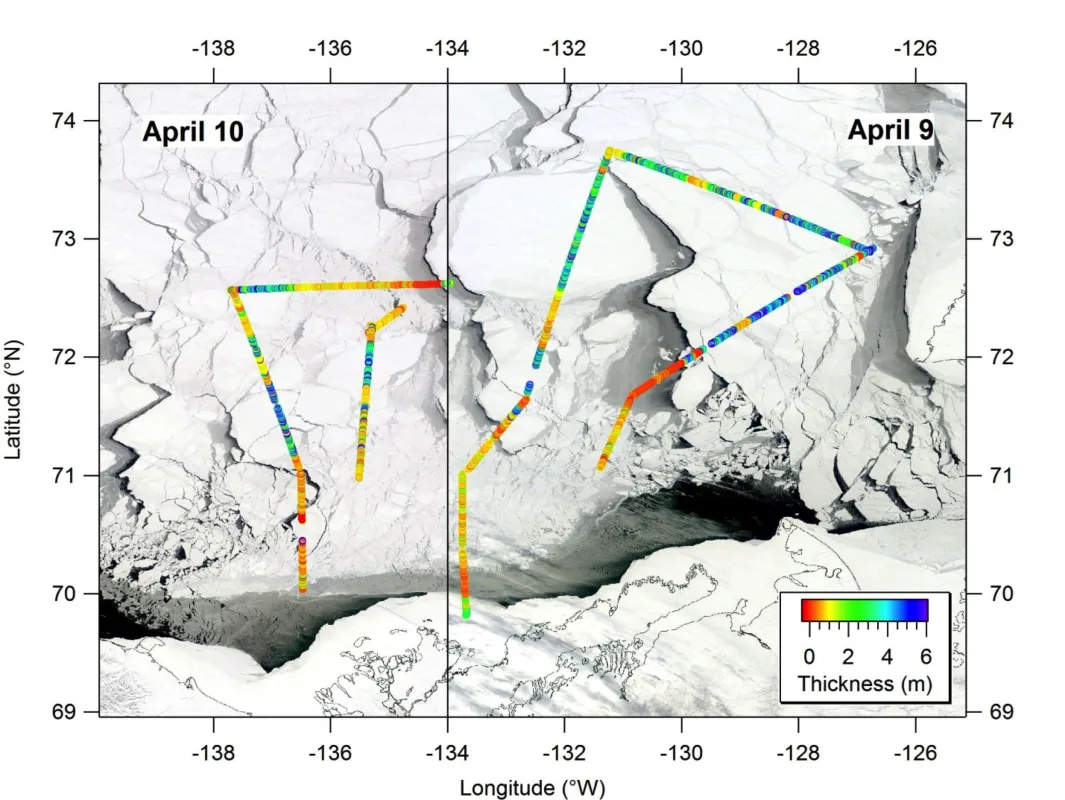

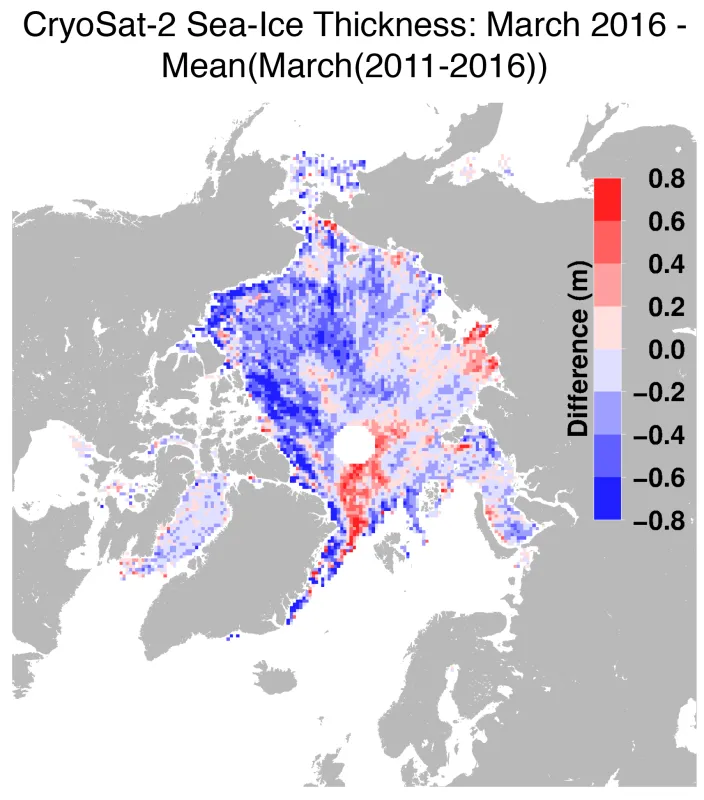

Satellite and survey data show that ice thicknesses in parts of the Arctic are similar to those observed in 2015, but that ice thickness over the whole region is thinner compared to the last five years. Ice thickness surveys carried out by York University in early April 2016 show that thicknesses in the Northwest Passage are similar to that in 2015, though there is less multiyear ice in 2016. In the southern Beaufort Sea, the thickness of multiyear ice is also similar to the previous year, but because of strong divergence and export, first-year sea ice is considerably thinner than in 2015, giving rise to expectations of earlier melt out of this thin ice and formation of open water in 2016. Data from the European Space Agency’s CryoSat-2 satellite show that first-year ice in March 2016 is thinner compared to the March 2011 to 2016 average, especially in the Beaufort Sea (20 to 40 centimeters thinner) and the Barents and Kara seas (10 to 30 centimeters thinner). Multiyear ice north of Canada and Greenland is also thinner.

The thinner first year ice may partly explain the early development of open water in the southern Beaufort Sea for this month. The multiyear ice on the other hand may survive and slow down the overall retreat of the ice edge, as it did in 2015 when a band of multiyear ice survived throughout most of the summer. However, the multiyear ice regime this year seems more fragmented and interspersed with thinner first-year ice. When this thinner ice melts, dark open water areas may grow rapidly as energy is absorbed which in turn melts more ice and can accelerate multiyear ice decay.

Fragmented ice in the Beaufort Sea

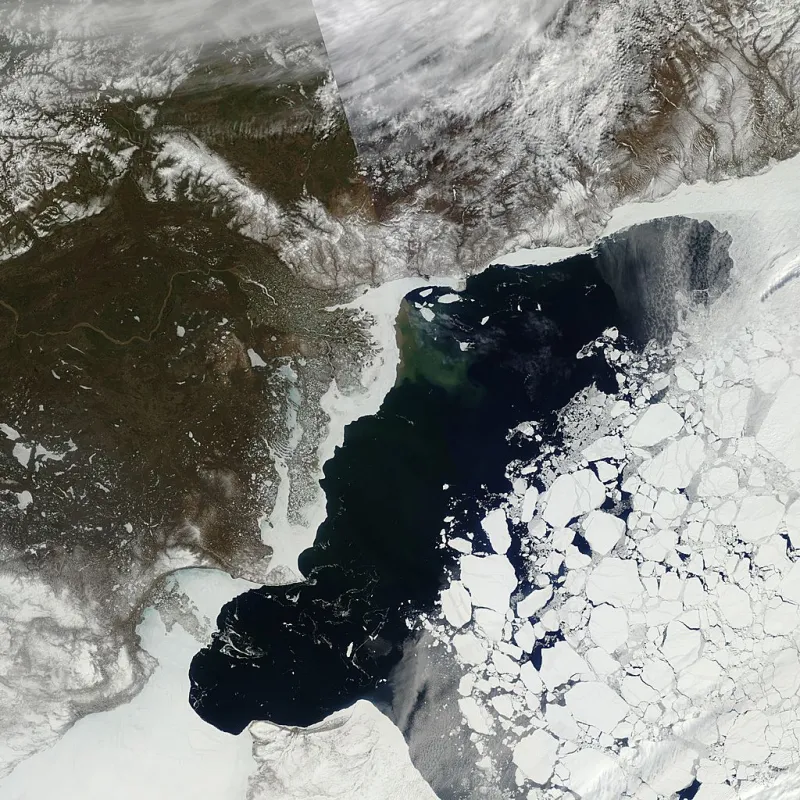

As discussed in last month’s post, a large area in the Beaufort Sea shows a very fragmented ice cover as a result of strong wind-driven divergence throughout the late winter and spring. Figure 5 shows a MODIS visible-band image from May 21, 2016 for the southern Beaufort Sea, illustrating how the fragmentation has led to large multiyear ice floes surrounded by first-year ice and open water. The area of fragmented ice now nearly reaches the pole. While thick, multiyear ice can better survive the summer melt season, the early development of open water allows temperatures in the ocean mixed layer (top 20 meters) to rise, which may enhance lateral ice melt in that region. In summer 2007, early retreat of sea ice from the coasts of Siberia and Alaska, combined with unusual clear skies, led to enhanced melt of thick multiyear ice floes, some recording nearly 3 meters (10 feet) of bottom melt. If atmospheric conditions this summer are as favorable as they were in 2007, some of this multiyear ice may not survive the summer.

Report from the field: Barrow, Alaska

NASA research scientist and NSIDC Arctic Sea Ice Analysis contributor Walt Meier spent the last week in Barrow, Alaska taking part in a National Science Foundation-funded sea ice camp and workshop. The goal was to bring together modelers, remote sensing scientists, and field researchers to understand each other’s work and to develop new ways to collaborate and combine knowledge about the Arctic sea ice system. As part of the camp, groups trudged onto the ice daily to take measurements. They found the ice to be quite thin at 80 to 100 centimeters (31 to 39 inches), compared to an average year when thicknesses would be 140 to 150 centimeters (55 to 59 inches). Melt ponds had already formed, though during cooler days, there was some refreezing as well. The residents of Barrow conveyed that it has been a very unusual winter. Normally, there is quite a bit of onshore wind from the west. This pushes the ice together and grounds pieces to the shallow shelf offshore, which helps stabilize the ice cover. However, this year the winds have been almost always from the east. This keeps the ice near the shore flat and undeformed (which the group observed during the camp) and opens up leads, or areas of open water, at the edge of the fast ice, which is clear in satellite imagery. This westward flow is a part of the larger Beaufort Gyre flow that has dominated the entire Beaufort and Chukchi sea region for much of the winter.

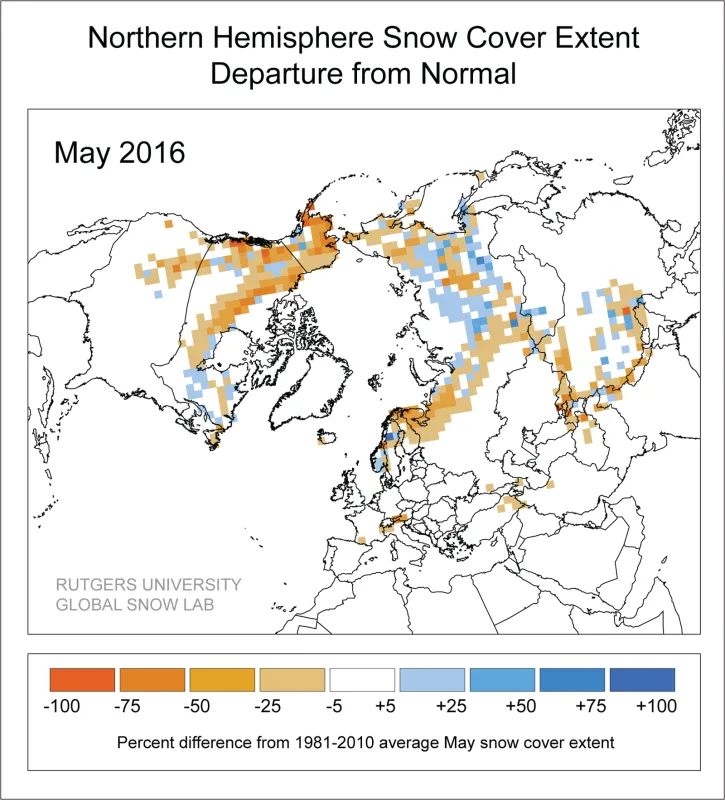

Record low snow

The Northern Hemisphere had exceptionally low snow coverage for both April and May of 2016 and a record low spring (March, April, and May), as reported from 50 years of mapping by Rutgers University’s Global Snow Lab. April’s snow cover was the lowest at 27.91 million square kilometers (10.78 million square miles), and May was the fourth lowest at 16.34 million square kilometers (6.3 million square miles).

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced on May 20 that Barrow, Alaska recorded the earliest snowmelt (snow-off date) in 78 years of recorded climate history. Typically snow retreats in late June or early July, but this year the snowmelt began on May 13, ten days earlier than the previous record for that location set in 2002.

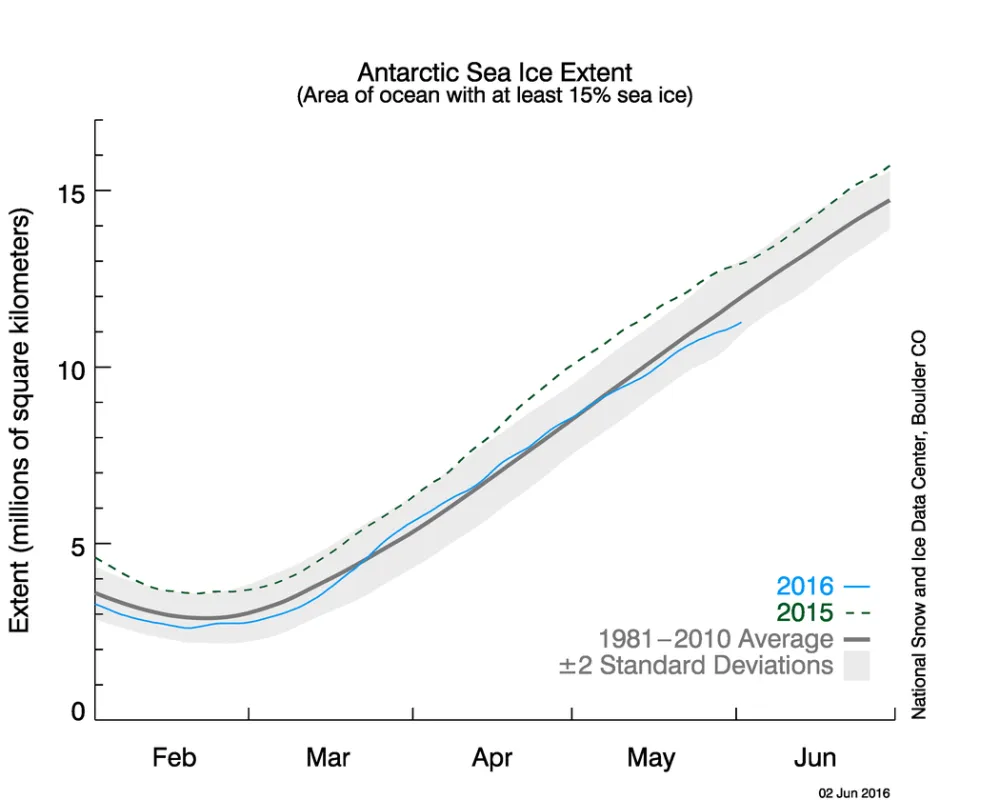

Below average sea ice in the Antarctic

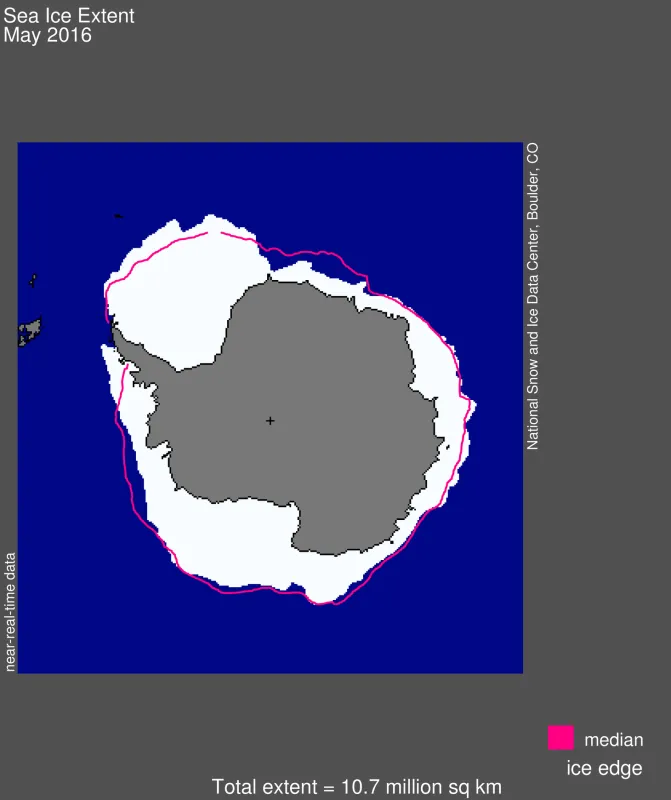

Sea ice extent in the Southern Hemisphere grew fairly slowly in May compared to the average, causing it to dip below the long-term average by the second half of the month. Antarctic sea ice extent for May 2016 averaged 10.70 million square kilometers (4.13 million square miles). This is 90,000 square kilometers (35,000 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 long-term average of 10.79 million square kilometers (4.17 million square miles). Antarctic sea ice has been trending at near-average to below-average levels since June of 2015. In May 2016, extent was particularly low in the Bellingshausen Sea, Fimbul Ice Shelf area, and Wilkes Land Coast, but well above average in the northwestern Weddell Sea near the Antarctic Peninsula.

References

Haas, C. 2012. Airborne observations of the distribution, thickness, and drift of different sea ice types and extreme ice features in the Canadian Beaufort Sea, Proceedings of the Arctic Technology Conference ATC, Houston, Texas, December 3?5, 2012, Paper No. OTC 23812, 8 pp.

Haas, C., and S. E. L. Howell. 2015. Ice thickness in the Northwest Passage, Geophysical Research Letters, 42, doi:10.1002/2015GL065704.

Perovich, D. K., J. A. Richter-Menge, K. F. Jones and B. Light. 2008. Sunlight, water and ice: Extreme Arctic sea ice melt during the summer of 2007, Geophysical Research Letters, 35, L11501, doi:10.1029/2008GL034007.