By Audrey Payne

Among the mountains of evidence that climate change is warming Earth faster than any other point in recorded history is the fact that most glaciers around the world are shrinking or disappearing. Melting glaciers and ice sheets are already the biggest contributors to global sea level rise, and according to the World Glacier Monitoring Service, ice loss rates have increased each decade since 1970. Yet, of the approximately 200,000 glaciers in the world currently, no database exists to identify which glaciers have disappeared, and when. The Global Land Ice Measurements from Space (GLIMS) initiative, an international project designed to monitor the world's glaciers primarily using data from optical satellite instruments, aims to change that.

“Glaciers are indicators of climate change because they grow and shrink on longer timescales than rapidly changing weather, so they give a clearer signal about climate,” said Bruce Raup, a senior associate scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) and director of the GLIMS initiative. “We know that glaciers are disappearing, but we’ve had no way to show that to people. So, we are making an effort to document glaciers that have disappeared and approximately when they disappeared.”

Identifying extinct glaciers

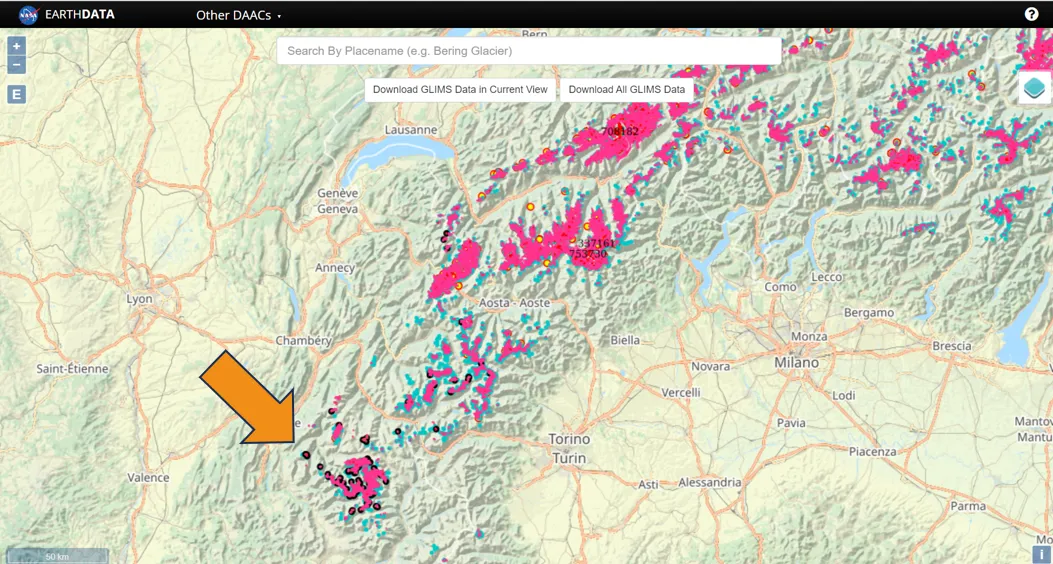

Raup, in collaboration with the GLIMS initiative, is working to identify glaciers that have gone extinct within the past few decades. He is doing so by gathering expertise from community partners at regional centers around the world and displaying this information via a new layer added to the GLIMS Glacier Viewer. “This new layer and data collection are an attempt to understand how many glaciers around the world have disappeared,” said Raup. “If I had to guess, I would not be surprised if 5 to 10 percent have disappeared over the last 50 to 80 years. But the reason that we want to have this additional data in the database is so that we can answer that question more precisely.”

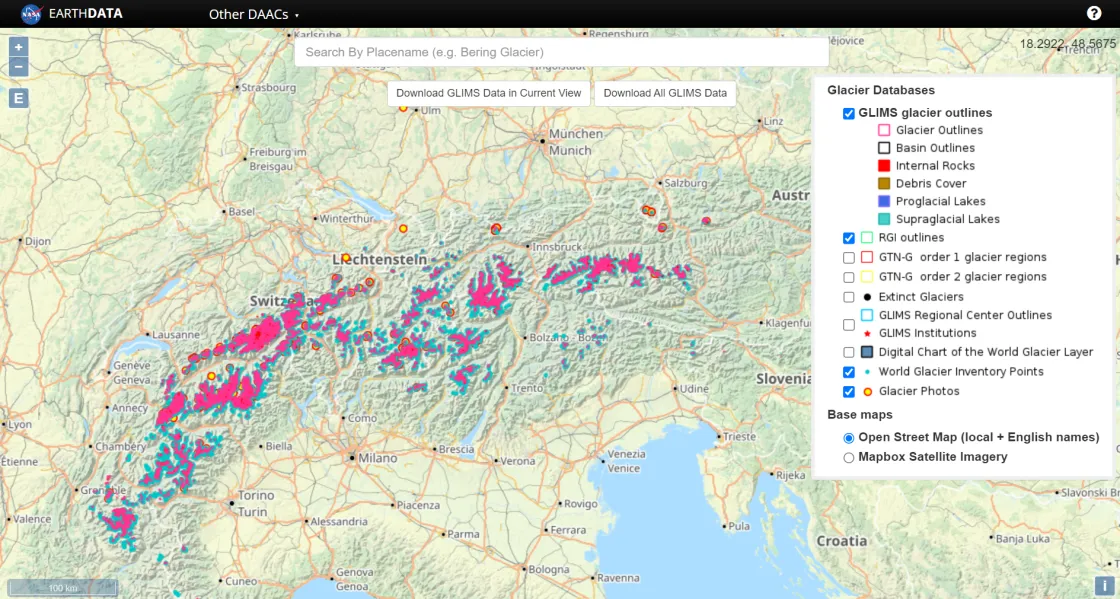

The glacier viewer is an interactive, multitemporal map showcasing the information held in the GLIMS Glacier Database, which is managed by the NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center (NSIDC DAAC) and contains data from nearly all the world's glaciers. The database includes measurements of glacier geometry, glacier area, snowlines, supraglacial lakes and rock debris, and images of glaciers from the NSIDC Glacier Photograph Collection, all of which are reflected in the layers that users can add to the GLIMS Glacier Viewer.

“GLIMS is a database of glacier outlines covering the whole globe and through time,” said Raup. “It is the go-to place for glacier outline data; there’s really no other source like it. So for anyone with any interest in glaciers, they come to GLIMS.”

He notes that a wide variety of audiences use GLIMS, including researchers, teachers, students, and those from private industry. A popular product derived from GLIMS is the Randolph Glacier Inventory (RGI), which rather than showcasing glacier outlines through time, more simply gives a snapshot of glacier outlines at a specific target date. RGI was recently updated to version 7.0, targeting the year 2000. RGI is popular among scientists modeling glaciers and their contribution to sea level rise.

Adding data bit by bit

Because GLIMS relies on input from community partners, the information on extinct glaciers is coming in and being added to the database and glacier viewer bit by bit, rather than all at once. “So far, I’ve been able to populate the database with disappeared glaciers from the Pyrenees, the French Alps, Ellesmere Island in Canada, and Mount Rainier in Washington State,” said Raup. “We know that more glaciers have definitely disappeared, like in Glacier National Park and Iceland, so it’s an ongoing task of getting the data and adding it to the database.” The extinct glaciers are identifiable in the glacier viewer by a simple black dot, though Raup hopes to improve the display in the future.

Raup has also designed the glacier viewer so that specific information about the extinct glaciers is accessible by clicking the relevant dot or outline on the map. This includes the glacier name, when it disappeared, who did the analysis, what methodology they used, and more.

“Adding these extinct glaciers to the glacier viewer has taken several steps,” said Raup. “It’s a work in progress. But we decided that because of the role that glaciers play as indicators of climate change, it’s important to document the death of them as they disappear, so that’s what we’re doing.”

Access data through the NSIDC DAAC

NASA’s NSIDC DAAC manages, distributes, and supports a variety of cryospheric and climate-related datasets as one of the discipline-specific Earth Science Data and Information System (ESDIS) data centers within NASA’s Earth Science Data Systems (ESDS) Program. User Resources include data documentation, help articles, data tools, training, and on-demand user support. Learn more about NSIDC DAAC services.