By Agnieszka Gautier

Nearly 20,000 shaggy and plump sheep wander the rolling, verdant hills of southern Greenland. During the short, mild summers and early fall season, they forage on grasses and tundra before herders gather them into barns come winter.

But in November 2021, snow in South Greenland had already shrouded the ground when heavy rain fell unexpectedly, forming a thick layer of ice. Not all sheep had been corralled, and fetching them across vast, rugged terrain proved nearly impossible in those icy conditions. Sheep were not only caught in the elements, but unable to break past the ice crust to graze on the vegetation beneath the snow. As a result, hundreds of stranded sheep perished following this rain-on-snow event.

Bruce Forbes, a research professor at the University of Lapland, Finland, and part of the international Arctic Rain on Snow Study (AROSS) project, led by the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), was paying especially close attention to the event. AROSS aims to quantify rain-on-snow and other extreme precipitation events, assess their impacts on linked social-ecological systems, and determine if their frequency, once a rarity in the Arctic, has already accelerated and by how much. Forbes said, “The better we understand these rain-on-snow events and how they are changing, the better prepared we will be to mitigate the challenges that come along with them.”

When AROSS began in 2020, the National Science Foundation-funded project focused primarily on Arctic regions like the Yamal Peninsula in Siberia, Finland, and Alaska. The project monitored extreme weather events, hoping to gather enough data to better predict their future occurrences.

When Forbes heard about the circumstances behind the loss of Greenland’s sheep, he recalled a rain-on-snow event that led to the starvation of 61,000 reindeer on the Yamal Peninsula just eight years prior. That winter in 2013, the reindeer were also unable to break through the ice layer to access nutritious lichen and grasses. Many migratory reindeer herding families amassed unrecoverable losses, with some herders never returning to their trade. Forbes had spent 32 years building close relations with the herding families that were directly affected, but like many western researchers, he was forced out of the region when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022.

Forbes had been aware of rain-on-snow events affecting reindeer in Lapland and Alaska, but hearing about sheep facing the same demise in southern Greenland surprised him. “The same thing is happening in different contexts in different parts of the Arctic,” he said. AROSS wants to document these interconnected experiences. “We want that direct interchange between Indigenous peoples from different parts of the Arctic to share their experiences with things they’re dealing with,” he said. Forbes, along with other members of the AROSS project, believes knowledge exchange may foster problem-solving techniques for all types of Arctic herders and communities.

A not-so green land

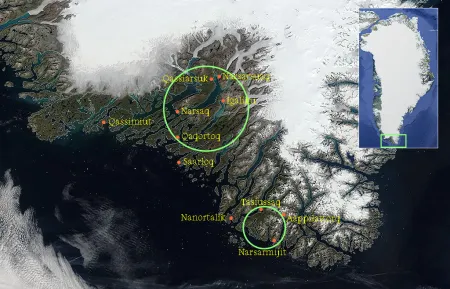

The region known as South Greenland, home to approximately 6,300 people, or 11 percent of Greenland’s population, occupies only the very southern tip of the giant, ice-capped island. Secluded villages dot the valleys between undulating hills. Majestic fjords cut deeply into the coastline with few roads carving the landscape. Even all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) and snowmobiles cannot reach certain remote places, so sheep herding—often a group effort—requires trekking up to 30 kilometers (19 miles) a day for a week or more to shelter the flock. The unforgiving terrain makes herding impossible when weather does not cooperate.

For instance, in 2023, even though no ice crust topped the snow, herders were defenseless against an overnight blizzard. “By morning, a lot of the sheep were actually physically buried,” Forbes said. So, any combination of extreme precipitation, whether it is rain on snow or heavy, wet snow, can cause lots of problems. “I’m afraid it’s the new norm that getting through a winter without it going above zero Celsius and raining is not an outlier, but the norm,” he added.

Sheep herding in southern Greenland has a rich history. Southern Greenlanders celebrated the hundredth anniversary of the reintroduction of sheep herding onto the island in 2024. “Many southern Greenlanders are Inuktitut-speaking Inuit,” Forbes said. Sheep herding began with the Vikings, who named the island Greenland to attract more settlers. Exiled for murder, Eric the Red first crossed the northern Atlantic Ocean from Iceland to southern Greenland in 985, bringing the first Norse settlers. At about the same time, Inuit traveled from northern Greenland down the western coast. As a pastoral culture, the Norse quickly introduced cows, pigs, horses, and sheep to the world’s largest island. The Norse thrived in the harsh terrain, with a short growing season and brutal winter, for over 500 years but then vanished, leaving behind a foundation of sturdy stone manors and churches in almost every fjord, valley, and within the steep mountains.

Colonizing the colonizers

To this day, no single theory explains why the Norse disappeared from Greenland, but while they vanished, the Inuit survived. One dominant difference between the cultures was the Inuit’s hunting technology and thus greater accessibility to diverse marine food sources when drought and colder weather persisted for decades.

In the late eighteenth century, Inuit Greenlanders began experimenting with agriculture in and around the foundations of abandoned Norse farms. In 1906, Pastor Jens Chemnitz introduced sheep from the Faroe Islands, just like the Norse had introduced them nearly a thousand years earlier. Then, in 1924, Otto Frederiksen reestablished a modern full-time sheep farming community at Qassiarsuk, the original site of Erik the Red's farm complex, Brattahlíð. At its peak, 60 farms herded sheep for wool and meat production, shrinking to some 37 isolated farms today. Scattered over hundreds of kilometers, these farms contribute to more than 80 percent of Greenland’s agricultural income.

Inuit sheep herders live only in southern Greenland and differ in their cultural practices from Inuit in western and northern Greenland, who do not farm. Forbes added, “They say, ‘Yeah, we were colonized, but we're here doing what we want to do because we like it. We have a high quality of life.’”

Present-day Inuit herders first learned about rain on snow events from their parents and grandparents’ experiences. During the 1966-1967 and 1971-72 winters, rain on snow hit coastal Greenland, killing two-thirds of the then 45,000 sheep population. To avoid potential future catastrophes, an agricultural reform mandated the stabling of sheep for seven months. But South Greenland has no local lumber supply. So, all materials needed to be shipped in to build barns, fences, and corrals. It took time to get the barns up, but the proposal, borrowed from European practices, was a good strategy for unusual weather events.

But now the climate is shifting even more dramatically. “They're having hotter summers, longer falls, snow coming later, more snow at difficult times, rain on snow, extreme snow. So, everything's going on in ways that people aren't used to,” Forbes said. “It’s beyond what they've heard from their own families and oral histories.” Greenland’s sheep herders are not only isolated on the island, but they are on their own in terms of management. Since Greenland gained home rule in 1979, the EU no longer intervenes in their pastoral practices like it does for other Indigenous communities in Europe.

Modeling a cultural landscape

Without a firm support system in place, it is critical that Greenland’s sheep herders can communicate with other livestock caretakers about ongoing threats to their herds like rain on snow events. Knowledge exchange was a vision within AROSS in its infancy—the goal being to invite and pay for Inuit Greenland herders to Finland to hear strategies from Sami reindeer herders, or one day to the Yamal Peninsula to speak with the Nenets people and their strategies for reindeer herding. “It’s learning by doing,” Forbes said. “It's more applications of what the possible futures might be through knowledge sharing.” Forbes hopes such planned knowledge exchanges, facilitated through AROSS, may help engaged communities solve problems. For instance, what is one community doing that another can learn from? Can experiences applied in Yamal be relevant to those in South Greenland? In addition, Forbes wants to use human stories to improve theoretical Earth system models, which often are key to determining herding regulation in Europe.

Every ten years, Europe’s regulatory plans for herders get updated to include new limitations on pastoral populations, which are measured using satellite imagery. Often there is an assumption that the wilderness is vacant, but though remote and seemingly untouched, satellite images show that Lapland, for instance, is just as much a cultural landscape as is South Greenland.

“There's very little ground-truthing [in Finland] and very little cultural or social input to improve an Earth system model, which is going to be part of policy decision making,” Forbes said. He confessed that he is not sure what adding human-land interactions into a model might look like, but gathering local human-use information is key to improving policies based on these models. AROSS may bring such stories to light.

One thing is certain—dramatic weather events are on the rise in Greenland, and throughout the Arctic. “We might be at a tipping point, which you can't tell when you're standing there,” Forbes said. So, a question remains: Can communities learn new tools and strategies to not only survive, but thrive? Here again, Forbes emphasized the importance of dialogue. “It helps to talk with people experiencing similar things,” he added. Similar experiences cross cultural landscapes with potential answers not too far away, just like the Norse who never learned key survival techniques from their nearby Inuit neighbors. “To get there requires putting aside assumptions, prejudices, and stereotypes of different cultural practices because the impacts of a less predictable climate are the same,” Forbes said. The key is to learn from each other when the unexpected becomes the norm. “So, the legacy of AROSS, hopefully, will be new relationships like this between the researchers and the pastoral people, because extreme weather is not going away.”

For more information

Historical video of sheep herding in Igaliku, Greenland (Filmed between 1950s to 1970s)

Arctic Rain on Snow Study (AROSS) project pages

References

Austrheim, G, Asheim, L-J, Bjarnason, G, Feilberg, J, et al. 2008. Sheep grazing in the North-Atlantic region: A long term perspective on management, resource economy and ecology. NTNU Vitenskapsmuseet Rapport zoologisk serie, no. 3, vol. 2008, NTNU Vitenskapsmuseet Trondheim, Trondheim.

Bichet V, Gauthier E, Massa C, et al. 2013. The history and impacts of farming activities in south Greenland: an insight from lake deposits. Polar Record. 49(3):210-220. doi:10.1017/S0032247412000587.

Northman, Jackie. 2019. "In A Warming Greenland, A Farming Family Adapts To Drought — And New Opportunities." National Public Radio. December 7, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/12/07/784557923/in-a-warming-greenland-a-farmi…