By Jane Beitler

In 2008, thousands of the world's polar researchers wrapped up a two-year, simultaneous research collaboration called the International Polar Year (IPY), and turned their thoughts to the future. Climate change is showing up fast and strong in polar regions, especially in the Arctic, where flora and fauna, and human ways of life, are beginning to change.

During the IPY, researchers collected an irreplaceable record of the polar regions at this time in history, studying climate patterns that no longer behave as they have for hundreds or thousands of years. But where will these data be fifty years from now? Will they be available and accessible for future scientists and other users? Sadly, experience from prior Polar Years in the 1880s, 1930s, and 1950s taught scientists that they must answer these questions before, during, and immediately after data are collected; much of the data from those IPYs were lost. If data are to remain intact for future researchers to study and reuse, something must be done now.

A space for polar data

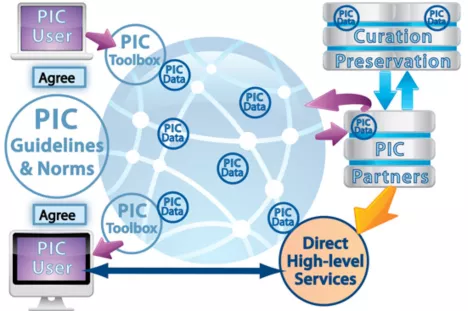

A single giant, central archive was not practical for these data, held in over sixty nations. Instead, IPY organizers and data managers dreamed of a collaborative, virtual space, where scientific data and information could be shared ethically and with minimal constraints. Inspired by the Antarctic Treaty of 1959 that established the Antarctic as a global commons to generate greater scientific understanding, they conceived of the Polar Information Commons (PIC). The PIC would serve as an open, virtual repository for vital scientific data and information. This community-based approach would foster data preservation and sharing, which in turn would support innovation and improved scientific understanding. Ultimately, IPY organizers hope it will encourage participation in research, education, planning, and management in the polar regions. Open access to data helps researchers understand and predict rapid polar change, and supports wise resource management and international cooperation on resource and geopolitical issues.

Norms, ethics, practices, and tools

Good scientific practice dictates a set of norms on data use, such as appropriate attribution, accurate description of the data, and community efforts to assure their quality. But how to implement this vision? The larger community lacked practical and technical means to enable, reinforce, and reward the right behaviors. Part of the solution was to build a suite of tools and services that make it easy for scientists to do the right thing. At the IPY Oslo Science Conference in June 2010, the international IPY Programme Office announced the launch of the Polar Information Commons to the community of polar researchers who had gathered to share science results from IPY.

The launch was supported by NSIDC's Libre (lee-bray), a project devoted to liberating science data from its traditional constraints of publication, location, and findability. Leveraging open-source technology and data management standards, Libre helps make it easy for scientists to make their data discoverable and usable by the whole world. For example, one Libre tool lets researchers easily create a graphical badge indicating that their data are part of the Commons, and describing any conditions for sharing.

Other Libre tools will include a simple tool to help others find your data, either via the Web or by depositing metadata in the PIC Cloud, an organized, virtual storage space built by Australian researchers for all types of polar data. Long known for its expertise as a centralized data repository, NSIDC is helping show the polar world how a collaborative, distributed data management scheme can be effective in stewarding scientific data for the long term.